Interview With Mireya Vela

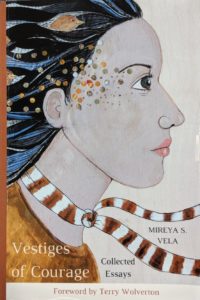

Mireya Vela! Strong, courageous, all around amazing woman! I met Mireya at Antioch and loved her immediately! She is a terrific writer and visual artist, activist, researcher and mom. Mireya has taken her experiences with childhood abuse and transformed them into art. Her current collection of essays Vestiges of Courage is a stunning testament to the healing power of words and to the need to end the silence in which abuse thrives. All the artwork gracing this interview is also Mireya’s. You can see even more of her work at mireyasvela.com.

I had the wonderful pleasure and honor of interviewing Mireya last August on FaceTime. It’s always great fun and inspiration to speak with my dear friend. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did!

Diane: Hello beautiful.

Mireya: Hi, how are you?

Diane: I’m good. You?

Mireya: Good. I’m in my room, the quietest room in the house.

Diane: Mireya. I’m so excited about your book! I loved it!

Mireya: You did?

Diane: I loved it!

Mireya: That’s great.

Diane: Loved it, loved it, loved it, loved it, loved it.

Mireya: There’s just one thing. My cat’s in the room with me, so you might hear him meowing once in a while.

Diane: Yay. You know I used to have 13 cats.

Diane: Yay. You know I used to have 13 cats.

Mireya: Did you really?

Diane: Yeah, I used to do animal rescue at a kill shelter. So, guess what. They all came to my live with me—the sickest, the crotchetiest, nastiest cats. It was wonderful.

Mireya: I only have two cats right now.

Diane: That’s enough.

Mireya: It is enough. I also have a rabbit.

Diane: I saw your rabbit. I used to have rabbits too. I love rabbits.

Mireya: I love rabbits.

Diane: They’re amazing. You have a little white fluffy one, right?

Mireya: Yes. I think her official colors are white and blonde. She’s got some blondish hairs in there. She’s really sweet. I’ve never had an animal that depended on me that way. It was a really interesting experience to pick her up and bring her home.

“I HAD A MOMENT WHERE I REALIZED THAT THIS GENTLE CREATURE WAS DEPENDING ON ME AND THE GRACE OF THAT WAS A LOT TO TAKE ON”

Diane: Tell me the story of the rabbit.

Mireya: OK.

Diane: We talk about everything in this blog.

Mireya: My daughter wanted a rabbit-

Diane: And how old’s your daughter?

Mireya: My daughter’s 10. She had wanted a rabbit for about five years, but we made her wait. We wanted to make sure she was mature enough to handle the care of a rabbit. Right around Easter we started looking.

Diane: That’s a good time.

Mireya: The best place to get them was at the shelter. A lot of people think, “Oh, I’m going to get a rabbit and it’s going to be great,” and they don’t understand the care that it takes.

Diane: A lot.

Mireya: Yeah.

Diane: The constant, little doodie balls.

Mireya: Yes. So, we looked up all of that and then decided, okay, I think we can do this, and then we went and picked up the rabbit at the shelter and when I was picking her up, I realized this wasn’t like a cat. She wasn’t going to defend herself. She wasn’t going to do any of that. She was going to be completely vulnerable. So, I cried all the way home. I had a moment where I realized that this gentle creature was depending on me and the grace of that was just a lot to take on. Of course, it’s gotten more and more complicated since, because the rabbit loves me back.

Diane: That’s beautiful. It’s a wonderful segue into your book.

Mireya: Can I give you some history?

Diane: Please.

Mireya: I grew up in a situation where animals were hurt. My grandmother was very cruel to animals. It was really weird. She would often get me pets and then hurt them. I don’t know whether it was a way to control me or it was just what she needed to do, but she was pretty awful with animals. Because of that I don’t have a tendency to have dogs because dogs don’t defend themselves in the same way. You know they cower, and they get small, but cats, cats will get you back.

I never had any of the more vulnerable animals.

Diane: So this was a big deal?

“I GUESS I HAVE SOME RESIDUAL FEELINGS ABOUT ANIMALS AND MY CONNECTION TO THEM”

Mireya: Big huge deal.

Diane: And tell me what it touched in you?

Diane: And tell me what it touched in you?

Mireya: I’m actually writing about it because it’s just been such a profound experience, to have this rabbit. I mean I know what it sounds like, it’s a pet, but at the same time it means a lot more. I guess I have some residual feelings about animals and my connection to them and the way they were treated.

And so, I’ve been having a very difficult time making peace with the fact that I loved these animals, that I brought them to the home and that they didn’t have an easy time.

I wasn’t in a position where I could protect them, and I didn’t know that I was going to need to do that. Our animals get you know, our cats, get the best of care. One of them recently was having a heart problem and spent some time in the oxygenated room, which is incredibly expensive.

And he’s not even a nice cat. He’s such an asshole.

Diane: I love it. I can really relate to that. I didn’t just have 13 cats. I had dogs, bunnies, everything. Mine was a little different … I was rescuing myself.

Mireya: Yes, I understand that.

Diane: I wanted the animal that no one else would want. He was going to come home with me and then when it didn’t fix me, I went and got another one.

Mireya: Well you have to keep trying.

Diane: Right. So that’s how my house became a little shelter. I stopped… Well this is debatable, but I stopped at the border of hoarding. I actually looked up animal hoarding to see if I qualified and I didn’t, but some people might disagree. I thought of writing about that too. It’s interesting. We have much in common, my dear.

Mireya: Yeah. Yeah. I imagine that it’s the same for me. I had no intention of having pets. When I moved in with my husband, he had two cats and I fell in love with them immediately, because I’m a sucker for animals. I’m glad I don’t work in a shelter.

Diane: That would be dangerous.

Mireya: Yes. It’s interesting because my husband and I have these conversations about how many animals I can rescue and he’s like, “No, two cats is enough.” And I’ll always tease him, I’m like, “You can’t put a limit on love.”

Diane: I know. We would have been dangerous together, I’ll tell you. Okay, so your book, Vestiges of Courage, is just stunning. It’s stunning.

Mireya: Thank you.

“TRAUMA … IT’S THE SAME THING OVER AND OVER AGAIN, IT’S LIKE A SCRATCH, LIKE IT’S SOMETHING THAT ITCHES … IF YOU’RE NOT DOING ANYTHING TO HEAL IT, YOU’LL ALWAYS FEEL THAT ITCH”

Diane: What struck me was the lyricism. Have you studied poetry?

Mireya: No. I mean I have a degree in English, that was what my B.A. was in. But I do feel like I hear certain music when I’m writing, so I kind of stick with whatever it is. Trauma works itself out that way sometimes. Like it’s the same thing over and over again, it’s like a scratch, like it’s something that itches that you need to scratch, and it keeps coming up. If you’re not doing anything to heal it, you’ll always feel that itch. And so maybe that is more musical for me? I don’t know.

But it wasn’t initially intentional because I wasn’t sure what I was going to write at the beginning. It just started coming out that way and then I think I had really good mentors that were just like, “No, no you got to go in this direction. No, see this beat here, you got to repeat that.” And it just happened naturally.

“I FOUND WRITING SO POWERFUL THAT I DECIDED I WANTED TO SPEND MY ENTIRE LIFE READING BOOKS AND MY LIFE BEING ABOUT BOOKS”

Diane: When did you start writing and when did you know that this was your thing? Or one of your things?

Mireya: I guess I must have been 13. I think most people that start writing early need an outlet. Somebody gave me a diary, and so I would write in there and it was always kind of this lyrical, poetic kind of thing.

I journaled my entire childhood and then into my teen years and into my adult years. Then when I was an adult, I had found writing so powerful that I decided I wanted to spend my entire life reading books and my life being about books, so I majored in English.

Diane: This book is a lot about trauma.

Mireya: It is.

Diane: Can you, for people who haven’t read it yet—I do say yet—can you just give us a little trauma synopsis? I mean, I don’t know how else to say it.

“YOU DON’T JUST GET ABUSED, YOU ARE PART OF A SYSTEM THAT SUPPORTS THAT ABUSE … EVERYBODY HAS TO BE WILLING TO KEEP THIS SECRET”

Mireya: I love that. The book is about childhood sexual abuse primarily and how that works itself out in my life.

I didn’t want to deal with it the way a lot of people deal with it. I didn’t want to just write about how painful it was. I really wanted to explore the systems that made it possible.

Because I have been in research for a really long time and I knew that you don’t just get abused, you are part of a system that supports that abuse, that makes that abuse possible. There have to be people that are willing to comply and people that are willing to be complicit.

And then you, as the child, have to be in a situation where you can’t get help. That’s what creates ongoing abuse. Also, the one thing I had learned more recently, since I had started doing research, is that you can’t sustain abuse in a loud space. A very important part of abuse is the silence.

Everybody has to be willing to keep this secret.

And that’s the way my family worked. I’m not sure that this is in the book, but I wasn’t the only person in my family who was abused. I was part of a system of girls that were abused.

Diane: That’s in there.

Diane: That’s in there.

Mireya: It is?

Diane: Oh yeah. The whole part about when you went to… here we call it CPS, Child Protective Service.

Mireya: Yeah.

Diane: Because the man who abused you was abusing some of your cousins?

Mireya: Yeah, it went back decades.

Diane: And your aunt as well she, who killed herself?

Mireya: Yeah, yes.

Diane: I’m guessing she’s … was a survivor.

Mireya: She was actually married to the abuser.

Diane: She’s the one who was married to him and then when she died and the girls were still left in the house, that’s when you called, right?

Mireya: That’s almost right.

Her sons were living in the house after she died and one her sons decided to move in a girlfriend who had children.

Diane: Right, and then she thanked you for calling.

Mireya: Yes. I don’t know what her situation was or how she perceived everything that was happening, but I didn’t want her little girl to get hurt.

Diane: When you did that, you were certainly protecting those little girls, but did you also feel like you were doing for yourself what nobody did? Was it healing for you?

Mireya: No. It wasn’t. The way that happened is that I was in therapy at the time and my therapist said, “I am reporting this. There’s no way you can keep silent on this.” And I was like, “I’m not sure I’m ready to go public.” And she said, “Well you don’t have a choice in this one.” So, she made the initial report and I contributed to it.

And it was a good call. You know it was the right thing to do.

Diane: Totally.

Mireya: But it was very scary.

Diane: Very scary. It’s very scary when you grow up in silence, to break that.

Mireya: Yes.

“SOMEBODY WROTE ME AN EMAIL AND THEY’RE LIKE, ‘HEY, HEADS UP, WE’RE NOMINATING YOU FOR A PUSHCART.’ AND I WAS LIKE, WHAT? AND I HAD TO LOOK IT UP”

Diane: So, explain to people what a Pushcart Nomination is.

Mireya: I’m not going to say that I know a whole lot about the Pushcart Nominations, but I was sending stories into publishers, different magazines. The Pushcart Nominations are designed for independent publishers to choose the stories they think are the best stories from those they’ve received throughout the year.

So, the first one that I got nominated for, floored me.

Diane: How’d you find out?

Mireya: Oh God, I think I got an email. Somebody wrote me an email and they’re like, “Hey, heads up, we’re nominating you for a Pushcart.” And I was like, what? And I had to look it up. I didn’t know what was going on and that was really, really shocking, because when you write, you don’t write to win a prize or to… Or even in hopes that somebody’s going to notice. Like you’re hoping somebody will but that’s not your goal. Your goal is to maybe, perhaps, connect with somebody.

Diane: And you had four nominations in one year?

Mireya: Yes, and I did have a meltdown over that.

Diane: Yeah, wow. That’s so amazing. Congratulations.

Mireya: Thank you.

Diane: And how did this book come about?

Mireya: The book came about in a really interesting way. The book has been published by The Nasiona, a small, independent publishing house. The main editor, the head honcho Julian emailed me and said, “Hey I found your website. Would you like to be interviewed for your artwork?” I said, “Oh, can you tell me more,” or something. And he goes, “Oh it’s right along the same lines of what we’re trying to accomplish. I would love to include your artwork in the magazine and interview you.” I was like, “Yeah, sure, that sounds really good.”

I looked them up. They were a social justice platform and that went along with my values. The whole interview thing happened and then at the end, I said, “Hey, you know, maybe I’ll try to submit stuff to you guys when I have a chance because I’m also a writer.” And they were like, “Wait, what?”

So Julian said, “Can you send me the manuscript.”

Diane: Wow.

Mireya: And I’m like, “Yeah.” So I sent it to him and I was starting to get the idea that this was going to be a book and that’s the way I was going to try to promote it, but I wasn’t 100% sure on anything yet, because with the arts nothing is a sure thing. You have to try one thing and then if that doesn’t work, you have to reimagine it and recompose it and whatever. He immediately offered me a book contract.

Diane: Oh my God. That’s amazing.

Mireya: It was… it was magic.

Diane: That is magic. Your book is magic. It’s beautiful. I didn’t want to forget about your visual art. So, tell me about when you started that. What is the difference for you? When do you choose to pick up a paintbrush and when do you choose to pick up a pen?

“I HAD TEACHERS THAT NOTICED I HAD SOMETHING TO CONTRIBUTE TO THE ART WORLD AND IT JUST FLOURISHED FROM THERE”

Mireya: I started drawing very, very early on like most kids, but I was very, very lucky in that I won an award when I was kindergarten.

Diane: That’s so cute. What was the award?

Mireya: I created this Dr. Seuss character, and everybody was really impressed, and I ended up winning a prize and it was like, “Hey, this is something that could bring me a lot of pleasure” and it’s a good outlet. I mean, now I realize it’s a good outlet, I don’t think I knew then. So, it kind of started that way and then I went into school and I had a couple of teachers that noticed my artwork.

Diane: That’s great.

Mireya: Yeah. That’s basically the way it happened. I had teachers that noticed I had something to contribute to the art world and it just flourished from there. I had a teacher who would advocate for me in the seventh grade. She was amazing. And then I had another teacher in high school who also advocated …You know what it’s fun, but it can also be very rewarding.

Diane: I want to get back to that, but I’m going to jump off something you said. You grew up in a family culture of silence, right?

Mireya: Mm-hmm.

Diane: And abuse and women were kind of … How would you describe the women?

“I HAD A LOT OF LECTURES ABOUT HOW I NEEDED TO BE QUIETER, I NEEDED TO BE BETTER BEHAVED … I NEEDED TO BE MORE ALLURING. NO, NO NOT THAT ALLURING, THAT’S TOO FAR”

Mireya: They were compliant.

I don’t think that all of them meant to be compliant. I think some of them were trying to do the best advocacy they could in their own way, but they were compliant. They belonged to a culture and a religion that told them for many, many years that they were there to be … to service men. That the Bible said that they were there to be in the service of men.

And so, I had a lot of lectures about how I needed to be quieter, I needed to be better behaved. I sat wrong, I dressed wrong. I needed to be more alluring. No, no not that alluring, that’s too far. And just basically, my household, in particular, was very religious. It was just a very oppressive environment where the women were trying to do the best they could in following their beliefs and trying to survive.

Diane: As I was reading your book, I wondered how you kind of broke this mold? How did you say no?

“I DON’T BELIEVE IN DOING THE RIGHT THING BECAUSE IT MAKES PEOPLE HAPPY. I BELIEVE IN DOING THE RIGHT THING BECAUSE IT’S THE RIGHT THING”

Mireya: My mom was very geared towards ethics and justice. These things really mattered to her, which is really interesting because she wasn’t able to uphold what she believed in, but she did believe in these things. She always talked about justice and equity and things of that nature. But I think for her they were just mostly ideas that she felt were right or cool or whatever. I took them very seriously. Both my brother and I are very justice oriented.

I think that at some point I found that center in myself. This is the way I figure out what’s right. I’m not religious but I’m very ethically bound.

And I don’t believe in doing the right thing because it makes people happy. I believe in doing the right thing because it’s the right thing. And I can see, now that I’m older, that probably was the way my mom was living her life too. It just happened that one child was not worth the survival of a family.

Does that make sense?

Diane: It does make sense. And what’s your relationship now?

Mireya: With my mom?

My mom and I don’t talk. We haven’t talked for over a year.

And when I tried sticking with my brother and then not talking as much to my mom, that didn’t work out, so I had to give up my brother and my mom and my dad.

Diane: That’s huge.

Mireya: Yeah.

“I CAN’T PRETEND I’M SOMEBODY THAT I’M NOT, AND I HAD BEEN PRETENDING THAT I WAS SOMEBODY THAT I WASN’T FOR A REALLY LONG TIME”

Diane: Did that have anything to do with the writing?

Diane: Did that have anything to do with the writing?

Mireya: It didn’t initially. So yes and no. No in that I always wanted to cut loose. I always wanted to leave that space because I can’t pretend I’m somebody that I’m not, and I had been pretending that I was somebody that I wasn’t for a really long time. When I’m with my family I have to act a little stupider and more humble, and I have to be more feminine and I have to be … It’s just like putting on a show and I just don’t have time for that stuff.

Diane: Isn’t that wonderful?

Mireya: You know I love it. I’m like, this is me.

Diane: We’re only here for this much time and when we get to the place where we realize that, it’s like I’m done with this … the pretending, right?

Mireya: Yeah. I don’t want to say that my family didn’t try to be supportive, because I think that in their own way they did. It just didn’t work.

I realized I had a lot of emotions about the way the things were happening in the family, and that in order to be in part of it, I had to continue to be silent and pretend like some things had never happened-

At the same time, I was writing about it, and being silent made me a liar. I couldn’t do that duality.

Diane: It makes you crazy. Not only a liar, right?

Mireya: Yeah, it just felt really messed up, so I think the most difficult part of this has been how I’ve had to manage my kids with the rest of my family. I have a husband who actually gets along really well with my parents.

Diane: Wow. Is he still talking to them?

Mireya: I don’t think he is, but I did have to explain to him, “Look I can’t do this dual thing,” and then he was good. But he is more likely to text them or respond to questions or whatever, and that’s the agreement we had. That he could act the way that felt best for him, but that I needed to take a really different direction.

Diane: So on that note, you were in abusive relationships before.

Mireya: So many.

Diane: How did you say goodbye to that? What was the turn? Because now you’re in a wonderful marriage?

Mireya: Yeah.

“THE FUNNY THING IS THAT I KEPT PICKING PEOPLE WHO WERE UNAVAILABLE BECAUSE I DIDN’T WANT TO BE IN A RELATIONSHIP”

Diane: That just doesn’t happen, right?

Mireya: I would say the way I got out of that is failure. Lots and lots of failure. I think it takes a certain acknowledgement that you’re doing something that’s vitally against the grain of what your goals are by picking certain people. The funny thing is that I kept picking people who were unavailable because I didn’t want to be in a relationship.

So when I met my husband, that was one of the questions that I had to really ask myself. Like, “Okay, if you’re going to commit yourself to this person is it because you really want to? Because you don’t have to anymore. You don’t have to be in a relationship. You don’t have to do anything to survive anymore. It’s really up to you.”

For example, I was very much in love with my ex-husband, but he was very, very emotionally unavailable, and he had an addiction problem. It’s really difficult to have a relationship with somebody when there’s addiction involved and that’s something I didn’t understand at the time. I’ve gotten to understand it with age and practice and failing and picking myself back up.

I did a lot of therapy and analysis of what my patterns were, so I could undo those patterns because I didn’t want this for my kids. I didn’t want them to have a mom that was getting beat up on a regular basis or to be in a space where things were not always stable or where there was danger.

Diane: So, you write about your son, right?

Mireya: He’s 24.

Diane: 24. Okay. Tell us about him.

“HAVING A KID ON YOUR OWN WHEN THEY HAVE SPECIAL NEEDS IS A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT EXPERIENCE … THEY’VE MEASURED THE STRESS LEVEL OF MOMS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS KIDS AND THEY’RE THE SAME AS VETERANS OF WAR”

Mireya: I had Nathan when I was young—for an American. I was 21, and I was in my last year of college, and I got pregnant. I didn’t really mean to be careless, didn’t really know what I was doing. It just kind of happened and then, before I knew it, I was in this really abusive relationship. But Nathan’s dad actually left right after Nathan was born, so I was in that relationship for a very short time.

In the process of being a mom to Nathan, I figured out that he had special needs. Having a kid on your own is really hard. Having a kid on your own when they have special needs is a completely different experience. You’re coping on a very different level. I think they’ve measured the stress level of moms with special needs kids and they’re the same as veterans of war. They’re always getting triggered; you never know what’s happening.

We didn’t get an autism diagnosis until he was 11.

Diane: Wow.

Mireya: Yeah, which is really late.

Diane: Yes.

Mireya: What I’m trying to say is that a lot of the times, even if you are working with children and you think you know what you’re doing and you have experience working with special needs kids, because I was a teacher who had experience working with special needs kids, you still are going to potentially mess up. All you can do is feel sorry and move forward.

We didn’t find out that Nathan had autism until it started becoming a bigger problem in school. Nathan’s amazing and he’s really smart. Because he’s amazing and he’s really smart and funny, he has the best coping skills.

“WE DIDN’T KNOW THAT ALL THESE DIFFERENT BEHAVIORS WAS HIM SAYING, ‘I NEED HELP AND I CAN’T HANDLE THIS’”

He’s able to work himself out of things in a way that I’ve never seen other people work themselves out of things. In fact, I like to tease him about the fact that I’ve never seen a better interpretation of the dead possum than when he’s trying to avoid something. I think it’s hilarious.

He’s able to work himself out of things in a way that I’ve never seen other people work themselves out of things. In fact, I like to tease him about the fact that I’ve never seen a better interpretation of the dead possum than when he’s trying to avoid something. I think it’s hilarious.

When he was 14, we put him in a school for autism, and that really changed things at home. Because a lot of his behaviors were about his inability to cope, and we didn’t know. We didn’t know that all these different behaviors was him saying, “I need help and I can’t handle this.”

Diane: Right.

Mireya: Once we got him out of the regular school system and into a non-public school, it actually really, really helped us.

Diane: That is clear in the book. I just have to tell you, you are such an amazing mother.

Mireya: Thank you.

“AS SOON AS I FOUND OUT I WAS PREGNANT, I PUT MYSELF IN PARENTING CLASSES. AND THERAPY”

Diane: You are such an amazing mother. When I read about him and when I’ve heard you talk about him. You just … I don’t even have another word, you’re amazing. I think that that’s even so much more impressive because you didn’t grow up with wonderful parenting models. Where did you pull that from?

Mireya: I actually have an answer for that.

As soon as I found out I was pregnant, I put myself in parenting classes.

And therapy. I think when anybody’s in a really difficult situation, you shouldn’t have to do it by yourself. I actually had a really good set of people that were helping me. I didn’t see it at that time because I felt so alone, but I see it now. I had people that were really rooting for me to succeed. The parenting class leader or the therapist I was working with. They would tell me what it was that I was supposed to be doing, and I would check in. It took me a really long time to figure out that my mom’s mothering practices were not normal, and so I would check in with the therapist, “Hey, this and that, is that normal?” And they would tell me, “Well, no.”

If your way of growing up was twisted, then you have to make sure that you’re not following the same patterns.

Diane: Absolutely.

Mireya: My mom didn’t agree with any of my parenting practices. And part of it was, well if it was upsetting her that much then I must be doing something right.

Diane: So that’s how you check-in.

Mireya: Sometimes.

But like there was this one thing that she and I both really, really struggled with. She helped Nathan with all of his homework and I … I know this is going to sound really horrible, but I needed him to fail at his homework.

Diane: I’m so with you on that. Oh my God. Tell me more.

Mireya: Well because if they can’t do the homework, they’re either not getting the lessons and they need extra support at school, or they need a different way to learn, or they’ve got a real severe problem, which is what we had. Nathan had a really difficult time with sensory integration, had a really difficult time with the muscles in his hand, so he couldn’t write the ABCs. It was really challenging. My mom would sit there, and she would do the ABCs with him and it would take hours, and I was just like, “He’s so miserable, you need to stop that.”

But when it’s your mom and your mom is not an easy person to deal with, you have to pick your battles. It was very challenging to parent when she was around.

Diane: About the parenting stuff, the way you write it, we can tell how brutally painful some of the things you guys went through. He’s miserable, how do we connect … But you’re so funny. And you have that balance and it’s beautiful, it’s wonderful.

Mireya: It is funny, right?

I’m going to tell you a story that’s not in the book. I have a friend who lives in Texas and her son also has autism and was going through the Texas school system.

She kept telling them that they were violating his civil rights and they’re like, “Hold on, hold on, we can’t possibly be violating his civil rights because he’s not black.”

Diane: Oh boy.

Mireya: It’s ridiculous what comes out of the school systems, so sometimes the only way you can deal with it is to consider that maybe it’s just funny.

I’m not saying that you put up with it. I’m not saying that you don’t let it guide what you’re doing, but I think at some point you kind of have to, you know-

Diane: You have to laugh, right?

Mireya: Yes.

Diane: So tell me… Your work life is so interesting. Are you writing full time now?

Mireya: I have kind of a hybrid thing going on.

I’m doing some consulting work with the county of Los Angeles. I was hired as a consultant by another consultant. I’m working with this group. We’re trying to figure out how to integrate the arts into the County of Los Angeles.

Diane: Wow, that’s neat.

“THEY HAD A MOMENT OF PANIC WHERE THEY REALIZED THEY HAD RUINED WHAT IS A VERY IMPORTANT HISTORICAL PART OF THE CHURCH. SO SHE CALLED ME UP AND SHE SAID, SOMETHING LIKE, “‘CAN YOU FIX THIS?’”

Mireya: Yeah, that’s been really interesting, so there’s that. And then I also, of course, write. Then I try to get painting or drawing in there as much as I can. Then there’s the whole mural thing-

Diane: Yeah, I see that on Facebook. What is this mural thing that you’re doing?

Mireya: It’s really funny. My friend, Angela, works for the Catholic church.

And they had a plumbing problem.

And they had to break open one of the walls.

And when they took the wall off, they realized there was a mural there from like 1939, 1940. And they of course, they had a moment of panic where they realized they had ruined what is a very important historical part of the church. So she called me up and she said, something like, “Can you fix this?”

Diane: That is so funny.

Mireya: Yeah. She sent me a text picture. She said, “Do you see this? What kind of paint is it? Could we fix it?” And so I set up some time to go and talk to her and assess what had happened to the wall and what would need to happen for it to look new, but old. Does that make sense?

Diane: Yes, yes.

“I GET TO WORK AT CHURCH. I’M TOTALLY LEONARDO DA VINCI”

Mireya: I told her what I thought the wall needed and she said, “Yeah come in, we want you to come in and fix it.” The expectations for the mural kind of shifted around a little bit. I finished the piece that I was supposed to finish a while back, but now they want me to touch up everything.

Mireya: I told her what I thought the wall needed and she said, “Yeah come in, we want you to come in and fix it.” The expectations for the mural kind of shifted around a little bit. I finished the piece that I was supposed to finish a while back, but now they want me to touch up everything.

So I’m now working with a tiny little brush painting each little piece by hand.

Diane: Wow.

Mireya: And then when I’m done with that, they’re going to want me to go higher up, towards the ceiling of the church, and then when I’m done with that, we are very aware there’s a mural on the other side.

Diane: Wow. So this is like Leonardo da Vinci, right?

Mireya: You know what, that’s what I keep telling my friend.

I get to work at church. I’m totally Leonardo da Vinci.

Diane: That’s amazing.

Mireya: That’s been a real adventure. One of the things my friend and I haven’t openly discussed, which is going to be part of an essay that I’m writing now, is how women are traditionally and historically not allowed on the altar, and the alter is currently my office.

So I’m at the altar all day and my friend is doing some very, very important work, trying to integrate women into the church in a different way. I think that it’s really amazing. She’s having to make space for herself at meetings so that the priests who are at those meetings with her, respect that she has something to say and that it might be worth listening to. But then there’s this whole other thing where she’s also bringing in people to repair the church who would normally not be allowed to repair the church.

Diane: That’s really exciting.

Mireya: Yeah, it’s really cool.

Diane: One thing I wanted to touch upon, when you were younger, you spent some time going back and forth into Mexico and back, right?

Mireya: Yeah.

“YOU’RE NOT GOING TO COME INTO A COUNTRY THAT DOESN’T WANT YOU AND THAT SEES YOU AS LESS THAN, UNLESS YOU HAVE TO”

Diane: What was that like being between the two cultures, and the two languages, and the two countries, and it must be killing you what’s happening today?

Mireya: It is.

My mom came here legally. My dad did not. What that ends up meaning is that you either have a connection with your family, because you can go back and forth, or you have no connection with your family because you can’t.

My mom’s family lives right across the border and she has a really amazing family. They’re loving, they’re gentle, they’re nurturing. I spent part of my childhood there. We would go back and forth. I don’t remember how many times a year exactly, but I know that for a block of time we were going every month. The cultural differences were really striking. And it’s not because it was American versus Mexican, it was because I grew up in my dad’s family and they were mean, and my mom’s family was not. It was really difficult to navigate and to almost have to switch personalities in order to get along with everybody.

I did live in a city in California where I was linguistically isolated, so I spoke Spanish first and then much later learned English. When I went back to Mexico my Spanish was okay, but it wasn’t as good as it could be, and then my English was okay, but not as good as it should be.

Diane: Do you want to say anything about what’s going on today?

Mireya: Yeah, I have a really difficult time understanding how people can’t have empathy. I mean you’re not going to come into a country that doesn’t want you and that sees you as less than, unless you have to, because your situation at home is very difficult. I think it’s really difficult for Americans to understand that because there’s infrastructure and systems in place here to protect people. The place where my grandmother settled, was rather isolated, and there was not any electricity at the beginning. Water came from the well. There was no infrastructure in place, where if somebody in the family got killed, they could go to the police and protect themselves. And I think that when many Americans think about what’s happening in other countries, they’re imagining those spaces as American spaces.

They’re thinking, “Oh you know they have an infrastructure, why don’t they just fix it. Oh, they have this, why don’t they just fix it?” No. It doesn’t work that way. In the part of Mexico where my grandmother settled, there are a lot of kidnappings. They kidnap and ransom people and there are a lot of really awful things happening that the police are not going to protect you from and can’t because there’s no system in place for that to happen easily. When people come here, it’s because they’re really hoping for something better.

They’re giving up their homes, which a lot of people feel a lot of nostalgia and love over, and they’re giving up their families, which they may never see again because those families are going to stay there, and you might not be able to get paperwork. You need your paperwork in line to be able to go back. I don’t think those people understand that it sometimes takes over twenty years to get your paperwork in order.

Diane: Wow.

Mireya: I’s not like you can just go and file for a green card and get it. They thoroughly analyze and investigate and there’s a backlog right now, so it might be years.

If somebody came to me and needed help, of course I would give it. There’s no question on a personal basis that I would do that, so I don’t understand why it’s so hard for people in this country, when this country is so, so rich in so many ways. Especially California, we have like the second biggest economy.

And then the other aspect is who you have to be after you are here and whether or not you’re accepted. If you have very dark skin, you’re not going to be accepted.

If you can pass then you’re accepted a little bit better, but you have to watch out for those mannerisms and the language and the accents and all of that stuff.

“ONE OF THE THINGS I THINK ABOUT A LOT IS WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOUR DREAMS AND YOUR ASPIRATIONS ARE MUCH BIGGER OR CAN’T BE HELD BY THE PEOPLE YOU GREW UP WITH”

Diane: Did you ever read the young adult book The Absolute True Story of a Part Time Indian?

Diane: Did you ever read the young adult book The Absolute True Story of a Part Time Indian?

Mireya: No, I haven’t read it.

Diane: Oh my God, now I know there’s some issues with the author with #MeToo stuff, but it’s really an amazing book.

Mireya: Who’s the author?

Diane: Sherman Alexie.

Mireya: What do you love about the book?

Diane: It’s about a kid who’s growing up on the reservation, who wants to go to the white school in the next town. He does, but when he goes there, he feels “half Indian.” When he stays on the reservation he feels “half white.” He has a hard time with that balance, and his friends on the reservation totally feel like he’s selling out and he’s abandoning them and that he thinks he’s too good for them. For the white kids, he’s not good enough. What does it mean when you want something more than you can get on a reservation?

Mireya: That’s really interesting, because I guess one of the things that I think about a lot is what do you do when your dreams and your aspirations are much bigger or can’t be held by the people you grew up with.

Diane: That’s right.

Mireya: And that’s something that I like been very, very aware of. It’s complicated.

Diane: It’s very complicated. You’ve managed to get free.

“I BELIEVE IN THE IMPORTANCE OF WOMEN. I BELIEVE THAT WE ARE VITAL AND THAT MORE THAN ANYTHING WE NEED TO BE PROTECTED AND LOVED”

Mireya: I did, but I had to give up a lot of people.

Diane: Did you feel like you were betraying people?

Mireya: Not betraying people. I was already in a space where people knew that I didn’t agree with them, that I wasn’t really buying into a lot of that stuff, that I really thought that the family culture needed a shift, that it needed to change and that was both on my mom’s side and my dad’s side.

And that I just thought that certain behaviors were completely unacceptable. That you didn’t make room for somebody to get drunk and get violent, but it’s okay because they were drunk. You know?

And I believe in the importance of women. I believe that we are vital and that more than anything we need to be protected and loved. And that’s not something my family could buy into.

Diane: What about abandonment? Did you feel like you were abandoning them?

Mireya: I definitely abandoned them.

I think I could have stuck it out and decided we’re going to change the culture. I’m going to start with our girls and we’re going to do this.

But I wasn’t going to do that.

Diane: Sometimes the problems just seem so big, right?

Mireya: They do. They do, and I think that my belief systems were just so radically different that there wasn’t a middle ground. This is a culture that thinks men are really important and I just don’t see it. I just don’t see it.

Diane: “I don’t see it.” I love that. I just want to go back to when do you paint. Is there a different calling for you?

“TRAUMA DOESN’T HAVE LANGUAGE, IT DOESN’T HAVE SEQUENCE, SO WHEN I’M PUTTING TOGETHER THINGS THAT HAPPENED AND THEN THIS HAPPENED AFTERWARDS, AND WHAT HAPPENED AFTERWARD, I’M ACTUALLY DOING SOMETHING THAT’S COMPLETELY HEALING FOR A PERSON WITH TRAUMA”

Mireya: Yes. Painting is a very different process than writing. They’re both basically about the same thing, right? It’s about me having a moment where I’m focusing on my internal life.

Whether it’s bad memories or feelings of nostalgia and wanting to be at a thousand places all at once because I didn’t get to do that when I was growing up. That’s part of the reason that I paint. I’m greedy, I want all of it. I want to imagine myself in a thousand places.

But the writing process is definitely more grueling, and it includes language. Trauma doesn’t have language, it doesn’t have sequence, so when I’m putting together things that happened and then this happened afterwards, and what happened afterward, I’m actually doing something that’s completely healing for a person with trauma. Because you’re putting sequence on this thing that happened to you that you only get in pictures and emotions.

So there’s that. And then the painting is different because when I am painting, I am tapping into this really, really different part of myself. In some ways there’s some overlap, but with painting, I just have to sit there and believe in myself for a few hours. I think that most women aren’t taught to sit there and believe in themselves for a bunch of hours.

It’s a revolutionary act. When a woman sits and believes in herself for an hour, it’s profound.

When I paint, I have a mantra. It’s basically me telling myself that I can do this and that I’ve done it before, and I can do it again and then I just follow the movement of my hands.

Diane: I’m excited to include some of your paintings! I just have to say this has been such a wonderful treat.

Mireya: Thank you.

Thank you for interviewing me and for finding interest in my work. A lot of times, people see this as a work of a certain group of people, but really I was hoping that it was something that could speak to a lot more people than that.

Diane: Oh my God, who doesn’t this speak to? Your writing speaks to the human condition. It’s universal. I mean people’s details may be different but much of our storylines are the same. (I think I lifted that from Pema Chodron.) If that makes any sense.

Mireya: No. I think that’s exactly right.

Diane: Thank you so much for sharing.

Mireya: Oh there’s one more thing.

Diane: Yes, please.

Mireya: I know my daughter’s going to get upset unless I mention that she’s 10 and she’s amazing.

Diane: Well I knew she was 10 because you did mention that. Tell her that you mentioned that.

Mireya: I will.

Diane: I have no doubt she would be amazing! Is she artistic?

Mireya: Yes.

Diane: And is she a writer?

Mireya: She’s not a writer. She’s really good at math and she’s really good at art. Yeah. My husband’s a math person. She excels in math.

Diane: I’m very impressed just hearing that because math and I do not get along very well.

Mireya: I think that’s the case for a lot of people, right? We have a bad experience at math at school-

Diane: And then you just say, forget it I’m not your friend and that’s it.

Mireya: Yep.

Diane: So good for her. She is amazing.

Mireya: Yes.

Diane: Yay. All right. So thank you, thank you, thank you. Love you.

Mireya: Love you too.

I hope you enjoyed getting to know Mireya Vela! As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! Please leave a comment or send me an email!

Have a wonderful week—see you next Friday!

Diane

Thank you, Diane, for another interview that was a joy to read.

Mireya, I am such of fan of the vulnerable warrior spirit represented in your art and writing.

There were so many quotable lines in this interview but I picked my favorite:

“It’s a revolutionary act. When a woman sits and believes in herself for an hour, it’s profound.”

Thank you,Sherry! That is one of my favorite Mireya quotes too!

Thank you for your kind words. I never thought I’d be this kind of woman. It’s a pleasure to share my growth as a person with other amazing women.

Diane, I don’t know how you do it, but you find the most amazing, inspiring, interesting woman to interview. Thank you.

Aww, thank you, Denise! I am so glad you are finding them so! Mireya is definitely all of the above!