Interview with Sarita Sidhu

Sarita Sidhu! I loved her the minute I met her. Sarita is not only warm and outgoing, she is high energy, highly intelligent, and Funny with a capital “F”! I met Sarita at Antioch University just two years ago, and in that short time, she has enriched my life beyond measure. Sarita is a woman of ideas and causes; she fearlessly calls out B.S. wherever she sees it. Growing up in a culture in which the sublimation of women and girls is the norm, Sarita’s outspokenness is no small feat! Join me as Sarita and I discuss how she found her voice … and learn about her arranged marriage, her move to the U.S., her environmentalism, and her dislike of ants!

I had the pleasure of interviewing Sarita on FaceTime in February 2019. It was the first time we’d spoken in quite some time, so we gush a bit in the beginning—forgive us! My only regret is that when you read this interview, you won’t be able to hear her delicious British accent! Enjoy!

Diane: I miss you. It is so wonderful to see you. I want to hug you.

Sarita: I miss you too. But I don’t miss all the deadlines in the MFA program.

Diane: Are you writing?

Sarita: I am writing, Diane. Finally!

Diane: What kinds of stuff?

“I felt what Bruce was singing. In theory, what the hell could we possibly have in common? Then I think there’s that universality right there. It’s in the lyrics, isn’t it? It’s the words”

Sarita: One of the things that helped me as I searched for a new framework post-MFA was thinking about Bruce Springsteen.

Diane: Interesting.

Sarita: I can’t even remember the first song of his I listened to, but it feels as though I’ve listened to him forever. He’s a storyteller. His music is so deep. It’s so real. I think the fact that he wrote about blue collar working life, about his dad and the factory―it reminded me of my dad. Aside from the grueling manual labor, I know my dad also faced a lot of racism at work and everywhere else in provincial England.

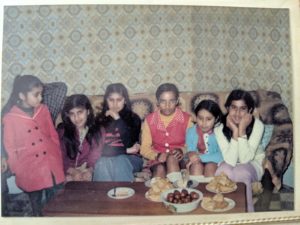

Picture from Childhood

He worked for Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, and I remember having to be quiet when he was on night shift because he slept during the daytime. I felt what Bruce was singing. In theory, what the hell could we possibly have in common? Then I think there’s that universality right there. It’s in the lyrics, isn’t it? It’s the words.

Diane: Yeah.

Sarita: So Bruce has given me a different framework within which to write memoir pieces. And thinking about the environment has given me another framework. I really do like having a sanitized life and just the idea of camping even is an anathema: “I’ve discovered beds now. Why would I go and sleep in a tent outside in the cold, where I could be attacked by wild animals?”

Diane: Or ants.

Sarita: Or ants. I try and exclude them from my house. Why would I go outside and join them? I don’t want to be in their company. This idea that we’re all connected. I know it more as an intellectual idea, and I know it’s really important, and I obviously get the impending climate catastrophe.

“I needed to be around to take care of them, the house, of everything, so I thought, “Well, what can I do?”

I came to writing after decades of not knowing what I wanted to do. Everything I did was not quite right. Working in the Fair Trade sector was different though, because I knew that it was a way to remake the world, albeit slowly. It got me out of the house, and it got me talking to people. It really got me out of my comfort zone.

Diane: Okay, can you just explain what fair trade is?

Sarita: I describe it as capitalism without exploitation. The deepest flaw within capitalism is that it allows people to exploit others. Fair trade puts a spotlight on the producers, and it makes people ask questions: Who made this? Under what conditions? Were they adequately compensated? Could they afford to pay for food, shelter, clothing, healthcare, send their kids to school as opposed to requiring them to help on the farm or wherever?

Diane: How’d you get involved with it?

Sarita: I became aware of the movement while living in England. The government got behind the Fair Trade movement in the UK and that helped raise its profile in the public realm. That’s one of the big differences between the UK and America. It always felt like the government was concerned about the well being of its citizenry, whereas here, the government seems to be centered more around what’s good for business, for corporations. There was this sense in the UK that we’re all in this together. When we moved here, to Virginia Beach, I couldn’t work.

Diane: You couldn’t work because you didn’t have a visa?

Sarita: My husband had a visa for work, but I didn’t, so I volunteered at the girls’ schools, and went to university, just took some graduate level classes, and then by the time we moved here to California, I had a green card, my husband was traveling a lot for his work and the girls were still young. I needed to be around to take care of them, the house, of everything, so I thought, “Well, what can I do?”

A friend of mind told me about our local farmers’ market here in Irvine, and yeah. Long story short, I ended up taking a stand there. I started out with coffee, tea, chocolate, brochures about the movement. Then it ended up being about 13 years. We tried to make Irvine a Fair Trade city and that didn’t happen.

“I’m not someone who can conform to cultural expectations when they limit freedom of thought and expression, the right to be an individual, to challenge sexist norms”

Diane: Wow, so you were trying to institutionalize Fair Trade?

Farmers’ Market

Sarita: Yeah, it’s a way to raise awareness. Here in the US, Fair Trade USA, based in Oakland, California, oversees campaigns to create Fair Trade towns and cities, churches, schools, colleges and universities. Claremont became the first Fair Trade City in Southern California in 2012, through the efforts of a coalition of local organizations including businesses, faith-based and secular groups, as well as concerned individuals.

Diane: How has your upbringing informed who you are? What was it like growing up?

Sarita: I think more than anything else, it eventually taught me who I’m not. I’m not someone who can conform to cultural expectations when they limit freedom of thought and expression, the right to be an individual, to challenge sexist norms. But my parents’ prerogative was to ensure their daughters didn’t do anything that would bring shame on the family-

Diane: Which would be pre-marital sex?

Sarita: Just if word got out that you had a relationship with someone.

“As we grew older, my friends were dating and socializing outside of school. That was really alienating because we couldn’t do that”

Diane: Any kind of relationship, like you couldn’t date?

Sarita: Oh, not at all. No dating. It was really strict―even what we wore, what we looked like. We couldn’t make ourselves look attractive in any way. My dad told us to focus on our school work … And that’s one of the really good things, that he didn’t stop us from studying just because we were girls.

My mom did sweatshop sewing at home. We had chores every Saturday and we would divide them up between us, but it’s funny, Diane; when it was my chore to sweep up in the living room, literally sweeping the dust off the floor, I couldn’t sweep it under the rug. I was conscientious. I had to get the dust pan and sweep it in there. That is probably a really good metaphor for my life. It’s really hard for me to not get to the root of everything, to not be a radical.

Diane: And expose everything to the light, right?

Sarita: Yeah. I don’t know how to leave something unexamined.

Diane: Growing up, did you go to Indian schools?

Sarita: Public schools.

Diane: You were exposed to other cultures.

Sarita: I had only white friends, but we weren’t allowed to socialize with them. It was school and home and never the twain shall meet. As we grew older, my friends were dating and socializing outside of school. That was really alienating because we couldn’t do that.

Diane: Right, because the peer group becomes so important.

Sarita: Yeah.

“On a recent trip back to England I was able to talk to my mom about the gender inequity in our culture, just give her a little bit of a feminist critique”

Diane: Did you have an Indian peer group?

Sarita: No, there was nothing. I mean, looking back, there was no one to talk to, which seems weird because I’ve got three sisters, but we never really confided in each other. Mom was pretty quiet, and I guess she was dealing with the fact that my dad was in charge and she didn’t really have much say in what went on either. We certainly didn’t.

Diane: Did you rebel?

Sarita: In small ways. Like removing my superfluous facial hair in secret because I was tired of walking around with a mustache and beard. I come from a collectivist culture and the responsibility for family honor rests on the girls and women. Meanwhile, my parents were surrounded by white females with the freedom to dress as they chose, go drinking and staying out late, and they were worried about arranging our marriages and providing dowries.

I come from a collectivist culture and the responsibility for family honor rests on the girls and women. Meanwhile, my parents were surrounded by white females with the freedom to dress as they chose, go drinking and staying out late, and they were worried about arranging our marriages and providing dowries.

On a recent trip back to England I was able to talk to my mom about the gender inequity in our culture, just give her a little bit of a feminist critique.

Diane: What was her response?

Sarita: She was surprisingly open to it.

“I told my mom we never blame the boys. We never blame the men”

Diane: Was this new to her?

Sarita: I think you know intuitively that these things are wrong, but you can’t vocalize it. Nothing in your environment supports your doubts about the social constructs that govern your life, keep you in your place. You don’t have the language to critique. This is why we owe a huge debt to the feminists who’ve laid the groundwork, given us the theory, the vocabulary. It’s still evolving, right?

Diane: Yes, yes.

Sarita: It’s always evolving. I told my mom we never blame the boys. We never blame the men. Just because women show the visible signs of a pregnancy, everything is their fault; the shame is theirs and they brought it on their family. My mom could see we let the boys and the men off scot-free, and it begins with pampering and celebration of boys, giving out Indian sweets when a boy’s born and then not doing that when a girl’s born, typically. But that depends on the community. And a lot depends on wealth and class.

Diane: But that was your experience.

Sarita: That was my experience. My mom and dad wanted a son, but they ended up with four girls.

“The first time we met, it was at a go-between’s house and we were allowed to go into a room by ourselves and talk”

Diane: We must talk about this arranged marriage my dear. What is that even like? How old were you?

Sarita: I had just turned 23 when I got married.

Diane: So tell me. Is this something growing up, like you say, oh my God, I wonder who my husband’s going to be?

Sarita: For me it was in the background, because my dad gave us the choice to get married or continue with our education. They hadn’t had the same opportunities in India because it was so expensive there. When I was 16 or 17, I became quite depressed and everything started to unravel when my dad said, “You can study. You can go to university, but it’s got to be local,” and I thought, “Well, if I can’t leave home, what’s the point?” For the first time in my life I lost interest in my academic studies and I fell behind. My academic success had been my only source of self-confidence.

Diane: Was it lonely?

Sarita: It was really lonely. I was confused and sad. But there was no one to talk to about my situation.

Diane: How long did you know your husband before you got married?

Sarita: About a year.

Diane: Okay, and were you supervised dating? Or how did that work?

Sarita: The first time we met, it was at a go-between’s house and we were allowed to go into a room by ourselves and talk. Then after maybe 20 minutes, half an hour, we were told, “That’s long enough. What else could you possibly have to ask each other?” To be honest Diane, I really just wanted to leave home.

Diane: And you were 22?

Sarita: I was 22 when we met.

Diane: Okay, and you were anxious to get out.

Sarita: I just wanted to get out. I had no social skills. I had no practice being assertive. Everybody else’s home looked better than mine at that time.

“Some time ago I decided I didn’t want my confidence to come from my looks. I wanted it to come from my personality”

Diane: Where’d you get your wonderful social skills?

Sarita: Thank you! I’ve acquired them over the years. Standing up for myself, for my daughters.

Diane: Were your daughters the impetus for you finding your voice or did you find it beforehand? Because you have your voice, honey.

Sarita: Some time ago I decided I didn’t want my confidence to come from my looks. I wanted it to come from my personality. I had to figure out what was important to me, and to then speak and act according to my values.

Diane: Did your husband grow up in the same traditions as you did?

Sarita: No, he’s a third-generation East African Indian.

Diane: Okay.

Sarita: And East African Indians are surrounded by a mythology of being more open-minded, more progressive and because he’s male, he had a lot more-

Diane: Freedoms, right?

Sarita: He grew up with so much freedom. He grew up so confident, so secure.

Diane: But did he grow up with this same vision of women? Because then he married you.

Sarita: I wasn’t like this at all. I was still trying to fit in. I was trying to be the good daughter-in-law who just listens and doesn’t speak and just follows orders.

“His mom made it clear when we got married that she was going to keep him with her forever, but I couldn’t do it any longer”

Diane: Because then you moved in with his family? Into his mother’s house.

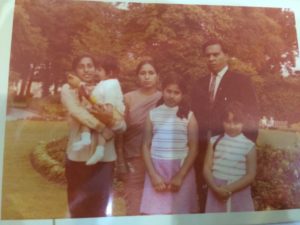

Sarita and Bob

Sarita: Yeah. Bob has two brothers and one sister. His sister grew up with all-male cousins too. She’s very assertive, and intimidating, and Bob’s mom was very strong, very controlling, manipulative. So he grew up surrounded by strong women.

Diane: Good.

Sarita: Bob’s very different from his brothers, who are more traditional.

Bob was brought up in the tradition of not questioning his eldest brother. We’re supposed to respect the elders unconditionally, both male and female. His eldest brother bullied me a few times after we married and I’d wanted Bob to stand up for me, but he didn’t.

Diane: When you moved to the United States, was that the first time you were out of somebody else’s house?

Sarita: No, we moved into our own house after five-and-a-half years. Ironically, it had been my mother-in-law’s idea that I become a teacher, and the B.Ed. program I enrolled in was taught by two strong women. Their focus was getting more girls interested in math and science and technology. For the first time I thought, “Wow, girls are important.”

Diane: You probably soaked that up.

Sarita: I really did. That program changed my life. I felt I had the right to ask myself what I wanted. More than anything else I wanted my own house. I couldn’t ask directly though. I’d learned that everything Bob said to his parents was well received; he couldn’t say or do anything wrong as far as his parents were concerned.

I’d get into it with his mom and end up looking like an idiot because I didn’t know how to approach her with anything I was unhappy about or felt was not quite right. Her usual response was, “Oh, you don’t understand. You’re too young. You misunderstood me. That’s not what I meant. It was not my intention.” I never got anywhere, and I’d just end up more frustrated afterwards.

I got to the point where I’d said to Bob, “I can’t have any more kids while we live here, and I want my own house.” His mom made it clear when we got married that she was going to keep him with her forever, but I couldn’t do it any longer. I had thought all I wanted was the freedom to wear whatever I wanted, get my hair cut, wear makeup, and nice clothes.

Diane: Did he come to her with that? That you wanted to move?

Sarita: He did.

Diane: Good for him.

Sarita: He did, and it was a shock. I know it was really hard for her. Then she put all these rules in place based upon her superstitions; the house we picked had to be a certain shape, only particular house numbers would be lucky, and so on. I thought, at this rate, we’re never going to find anything.

“I’d always wanted to study literature, and so this was my chance to look beyond the physical world, at the inner world, from a woman’s perspective”

Diane: But you eventually did?

Sarita: Yes. We bought the house we loved, even though it didn’t meet her stringent requirements. We lived in it for about seven years before we moved here.

It was separate, but my mother-in-law was still calling all the shots, so we weren’t as independent as I’d wanted to be.

Diane: But your move here. That was it, and that’s when you got exposed to … I know yoga was very important to you when you first moved here.

With Sister Simone Campbell on her most recent Nuns on the Bus social justice tour

Sarita: Yoga, and I took graduate classes: Feminist Thought and Women Writers. What I learned opened up my mind in a very big way. I’d always wanted to study literature, and so this was my chance to look beyond the physical world, at the inner world, from a woman’s perspective. That was huge. Life changing. It’s taken me a while to realize how significant that period was.

Diane: So you’re an activist in every cell of your body.

Sarita: Most of them!

Diane: Was it a gradual thing for you? When you had daughters, and you saw different possibilities for them, I would imagine that became more important.

Sarita: I tried to get involved with activists close to where we lived in West London, where there’s a big South Asian immigrant population. I wrote to them, but no one ever responded. I was able to build a life around activism after moving to California in 2003. I started with the Fair Trade movement. My husband found Democracy Now! on TV and I’ve never looked back. Independent news clears the obfuscation of establishment media outlets like National Public Radio and the British Broadcasting Corporation, which, for the most part, ensure the continuation of the status quo.

“Sometimes I think if I’d known I could be funny, because I had to have permission to think, even, I might have been able to change the dynamics in our house”

Diane: You’re also so funny! Were you always so funny?

Sarita: I don’t think I was funny. There wasn’t much to laugh about really.

Diane: Well, that’s when humor is most needed.

Sarita: It is, you’re right. Sometimes I think if I’d known I could be funny, because I had to have permission to think, even, I might have been able to change the dynamics in our house. If we’d had humor in our house, it would have helped a lot. I could have diffused situations, even though it wasn’t my job. It could have been really different for all of us.

Diane: When did you embrace that funny side of you?

Sarita: Maybe when I started teaching in England, after we moved into our own house. Then coming to America, becoming more politically aware, and then trying to set the tone for our daughters as well and just wanting to live a house in which we could laugh. Everyone is fucking hilarious in my family. I mean, I’m not saying that I’m fucking hilarious, but-

Diane: You are. You so are.

Sarita: Thank you. You are as well, Diane.

Diane: That you’ve got to own, really.

Sarita: Thank you. Bob is funny.

Diane: He is funny.

Sarita: Our two daughters are funny. They’ll have us in stitches. I think it just became okay to laugh.

Diane: That’s wonderful.

Sarita: This is the first joke I ever came up with, years ago: What do you call a Jewish person with a pH of one?

Diane: With a pH of one? I don’t know.

Sarita: Hasidic.

Diane: That’s so funny. You made that up?

Sarita: That’s the first joke I remember coming up with and I thought, “Okay. I think that’s quite funny, but I don’t know if it’s offensive.” I don’t think it is.

Diane: You know what? Today everything’s offensive. You know what I mean? It’s either everything or nothing. People get offended by everything or they don’t get offended by anything. There’s no sanity. I have to share this with you. I heard an interview with a Chilean filmmaker, Sebastián Lelio, who made three films that were very well received.

The first one was about a transgender person. The second one was about a lesbian couple in an Orthodox Jewish community.

“It’s definitely problematic when you have, let’s say, somebody white, who plays a role that should be somebody ethnic, when there are ethnic actors and actresses who could do it”

Sarita: Okay.

Diane: And the third one is about a middle-aged American woman. He got a lot of pushback for those movies, like “who are you to tell these stories?”

People told him that actors who aren’t transgender shouldn’t play transgender roles (the actor in his film was transgender), so, he asked if a transgender person shouldn’t be cast to play someone cisgender? I’m paraphrasing, but he said something like, “It’s a sort of fascism of the left. Limiting artistic expression is never a good thing. So many rules. ‘You can’t say. You can’t do. You can’t do this art. You can’t write this. You can’t produce this. You can’t paint this.’” I just thought it was interesting.

Sarita: It is, and I think he’s right.

Diane: Yeah.

Sarita: I can see where it comes from as well, especially with the lack of representation and-

Diane: Absolutely. He says it’s a response to the times, but it’s not the healthiest response.

Sarita: No, I think you’re right. It’s definitely problematic when you have, let’s say, somebody white, who plays a role that should be somebody ethnic, when there are ethnic actors and actresses who could do it. I wonder how hard casting directors looked.

Diane: Yeah, you want to open up the space for everybody—and cast for authenticity. Like when there’s a role about a famous person, you look for someone who looks like that person. Whether it’s race or facial structure or eye color or whatever.

Sarita: Yeah. But then you know, that is our job isn’t it, Diane? To support those people who are being told they cannot.

Diane: That’s right. It’s a very, very tricky place.

Sarita: It’s very tricky and you know what gets me? Mainstream TV, movies, advertising―ordinary people are absent, especially in the U.S. All we see are skinny, good looking, flawless people.

Where are the fat, ugly, normal people?

Diane: That’s right.

Sarita: Old people who look old, who fart―where are they? I want to see those people. Stop showing us these shiny people who are ridiculous.

“I’ve always asked the universe for guidance. So, I asked again, ‘What do I do now?’”

Diane: Okay, back to you honey. It’s about you. You are now 52?

Sarita: 55.

Diane: Tell me a little bit about what 50 means to you? Did you feel any kind of freedom or anything different and what brought you to the MFA and how has it changed you?

Sarita: I never knew what I wanted to do career wise. Living in England, teaching mathematics full time in high school, with two young daughters, I felt powerless, like I was failing at everything. I knew I didn’t want that life. My daughters are six years apart, and as they both left home to study, then work, I understood a chapter was closing, and I thought really hard about what I could do next. I picked up Dr. Christiane Northrup’s book again, The Wisdom of Menopause.

I was always drawn to her because she embraces alternative treatments and the spiritual, along with allopathic medicine. I believed Dr Northrup when she stated that if I didn’t do something bold, something different now, then I probably never would.

“You know what really did it for me? It was their maxim: ‘Community, Not Competition’”

I’d learned how to do Reiki in Virginia Beach 17 years ago. I’ve always asked the universe for guidance. So, I asked again, “What do I do now?” I was applying for jobs that I probably would not have been happy doing. I was really low balling everything, and then I saw ads for the MFA program at Antioch, and you know what really did it for me? It was their maxim: “Community, Not Competition.” I thought, “Wow.” I did some more research and saw they were rooted in social justice. I began to think “Oh, this might be a good place for me.”

I still wasn’t sure. I didn’t have a background in literature. I had so many doubts, and there are just these hurdles. I had been resistant to going through all these hurdles that you have to jump over in America.

Diane: Like what?

Sarita: My bachelor’s degree, I would have to have it evaluated. It was going to cost quite a lot of money.

Diane: Got it.

Sarita: But I decided to go through with that process. Then, the personal essay. I wondered what I could write. I hadn’t written anything for a long time.

Diane: But you were called to write?

Sarita: When I took the classes at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, a friend and I both had this idea that we were going to write books that would be in Oprah’s Book Club, and then we were going to be famous authors. Just so naïve.

Diane: What a wonderful plan.

Sarita: I actually did write a book, Diane.

Diane: You did?

Sarita: Mmm, it was self-published in 2005, and I thought, “Okay, I can write.” So I applied for the MFA. I sent all the paperwork in and when Steve called me and offered me the place, he said, “What would stop you from doing this program?” And I replied, “This has been the hardest decision of my life. Am I going to be wasting all this money? What am I doing?” I continued, “I think probably the amount of money it’s going to cost me, that might stop me from finishing the program, if I start it.”

Sarita: Mmm, it was self-published in 2005, and I thought, “Okay, I can write.” So I applied for the MFA. I sent all the paperwork in and when Steve called me and offered me the place, he said, “What would stop you from doing this program?” And I replied, “This has been the hardest decision of my life. Am I going to be wasting all this money? What am I doing?” I continued, “I think probably the amount of money it’s going to cost me, that might stop me from finishing the program, if I start it.”

“There’s no clear career path at the end of this at all and I could be wasting my time, wasting this money. But I might not, and it’s an investment in me. I need to try this. I need to do it.”

Then he said, “Well, we have a fellowship that gives you 25% off tuition.” I thought, “Oh, wow.” Because to be honest Diane, Bob was not on board with me doing this. As supportive as he is in general, he said to me, “If you can guarantee that you’re going to make up the money afterwards when you start working…” and I thought, “Well, fuck me. I can’t give you that guarantee.” I think if I had been earning more of my own money, even though Diane, I understand intellectually it’s a partnership. He can only do what he does because I’m at home, because I was with the kids. All of that intellectually-

Diane: But the bottom line is the bottom line, right?

Sarita: It is. I thought about it really hard again and I had to say to Bob, “I can’t guarantee anything. There’s no clear career path at the end of this at all and I could be wasting my time, wasting this money. But I might not, and it’s an investment in me. I need to try this. I need to do it.” Then he was okay with it. I said to him, “You can’t put that condition on me. That’s not fair.” Really, I had to give myself permission to waste money.

Diane: Well, it’s how you define waste, like how do you value money? That you make it back? That you make more than that back? Or how about just having a wonderful experience that you grow and heal through?

Sarita: Growing up with no money to spare, I had to have a really good reason for everything, so I’ve always been frugal. I dye my own hair. I always waxed my own legs when I was younger and waxed my sisters’ legs.

Diane: But you came to that place.

Sarita: I think the universe was guiding me. At the back of my mind I thought, “Well, if I go to the residency and I hate it, then I’m just going to discontinue.”

Diane: I went in with the same thing. I’m going to do one semester. I’m going to do one semester and reevaluate.

“I worked like a motherfucker, reading all the books, the analysis, trying to learn about craft/literary elements, literary terminology”

Sarita: But it’s been life changing, Diane, oh my God-

Diane: Yes.

Sarita: It was so fucking hard to do this, such a steep learning curve. Feeling intimidated. Feeling like I’m not good enough, I can’t do this.

Diane: Where did you get that from?

Sarita: I think it’s really old stuff, being a female, that you’re not good enough. You’re not as good as the men. Then being working class among the elitist literati. The sexism in literature and the wider world. In my culture. Growing up where I did in England, my dialect gives people a reason to look down on me. I joke about it. On my recent trip back to England I was really surprised when someone asked me, “Where are you from?” I said, “Can’t you tell? I’m from Wolverhampton.” I thought, “Oh, okay. I guess I’ve lost a lot of that dialect,” but it wasn’t through a deliberate effort to do so.

Diane: Yeah, well, you’ve lived in a different country for so long.

Sarita: It’s just another way to dismiss people, right?

Diane: I get that with mine, with my accent, you know.

So how did you grow?

Sarita: I worked like a motherfucker, reading all the books, the analysis, trying to learn about craft/literary elements, literary terminology.

Diane: Yeah.

“Everything was so hard. All the deadlines. And I just threw myself into it because if I’m going to do something, I work as hard as I possibly can”

Sarita: All of that. It was learning from the ground up: looking at my daughters’ high school literature books; acquiring the language to be credible, to be able to discuss. Then being encouraged to find my voice by Bernadette, my first mentor. She would say, “Well, what do you think about that?” And I thought, “Who am I to think anything of that? I don’t know enough yet.” But then my confidence grew. I wrote my book annotations and then I would look online to read what other people had written about them. I knew I’d made real progress when I disagreed with some of them!

And very importantly, the people, like you, the love and the community, the comradery, the support―this was all crucial to my learning.

Diane: I loved you. From the second I met you, we were in Bernadette’s room. Remember that? We were all together.

Sarita: Going around the room, introducing each other, telling everyone something they’d never guess.

Diane: That was my first project period and your second.

Sarita: And I talked with you about my knicker elastic―

That’s one of those tensions, isn’t it? Erin Aubrey Kaplan taught me about tensions, but regarding more serious things, like being alone versus lonely, liberated versus connected. But coming back to underwear― knickers―if it’s too tight, it’s uncomfortable and creates a muffin top, but if it’s too loose, well, then it’s going to fall down, isn’t it?

Everything was so hard. All the deadlines. And I just threw myself into it because if I’m going to do something, I work as hard as I possibly can.

Diane: Yes.

Sarita: Then at the end of it, the residency was a roller coaster, with wonderful highs.

Diane: Yeah.

Sarita: How my reading and the presentation were received.

Diane: It was beautiful. You did such a wonderful job and I’ll never forget Bob tearing up. That was just so beautiful.

Sarita: It was a surprise to him. I didn’t want him to know what I was going to read.

Diane: I know. That’s so funny. I love it. It was really great. And now you’re done, and I will be graduating this June, and I am so grateful that I met such a wonderful friend in the program. Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts and experiences with us today, Sarita.

If you’d like to read some of Sarita’s work–and I highly recommend that you do!–here are some links:

As always, I would love to hear your thoughts! Please post a comment or send me an email!

And have a wonderful week!

See you next Friday!

Diane

Can you all believe that Diane put this together while at her final residency? Of course we can!! I keep meaning to ask how much sleep she gets. I always think of RBG when I think of Diane- I’ve read that the supreme court justice only has a few hours sleep each night.

Massive congratulations on your graduation, Diane :))

Love you xoxo

Thank you to everyone who has read this interview.

Greta, thank you for your encouraging words. I concur that as women, we certainly have much shared experience. I became interested in Selma James, who founded the Wages for Housework Campaign. Because the work of women, everywhere, is the backbone of all economies.

Thank you, Nicky, for your thoughtful interaction. It’s always interesting how we each engage differently with the same information, depending upon what we already know and think. In my case, I see the tension between connectivity & loneliness within the context of distancing myself from my birth family & the ensuing turmoil this untethering has generated.

Thank you, Sarita, for your graduation wishes! I haven’t had much sleep lately, actually, as I’m still not used to the difference in time (East coast/West coast switch), so maybe this week, I resemble RGB–but no one can hold a candle to that she-ro for the long haul!!

Love you, and thanks again for embarking on the interview journey with me!! XO

Congratulations, Diane, on your graduation!

Your interview fits neatly beside the Melinda Gates book I’m reading, The Moment of Lift.

Sarita’s experiences–in becoming a woman entitled to think independently–mirror the lives of other traditional women: too much unpaid work in the home or being a working supermom;, and an early home atmosphere that discouraged questioning cultural norms.

What a success she is.

Thanks, Greta, for the graduation wishes, and thanks for reminding about Melinda Gates’ book–I’ve been meaning to pick it up!

Sarita is quite the success! I think we all need to give ourselves a heaping of credit for all the work that went/goes unpaid and/or for having been working supermoms–well put!

Hi Diane,

There were several insights in this interview that I loved. The first one was the idea that if nothing in the environment supports your doubts about the social constructs, you don’t have the language to do anything different. Brilliant! Another was the idea that debate is futile when there is no agreement on the facts. How true and how wonderfully articulated.

Perhaps the insight that gave me the most to think about was liberated versus connected. Oh my. As a card carrying two on the enneagram, connection is the ultimate value. Paring that as almost an opposite to liberation gives me lots to think about.

Thank you for this interview – I clicked through and read some of Sarita’s writing and enjoyed.

Your graduation is in a few days if I remember correctly. Hope you celebrate and enjoy every moment!

Thanks, Nicky! Sarita is full of wonderful insights! Thanks for sharing the ones that resonated with you!

And, yes, graduation is this Sunday–thanks for remembering!