Interview With Rebecca Kuder

Rebecca Kuder is a courageous writer, a woman who looks at the tough stuff in her life–and women’s lives–and doesn’t shy away! (Check out her essays “Hot Thing” and “Hot Thing #2 (2:30 a.m.)” about menopause!) We talked about her writing, about mental health, about trauma, about bodies–and the importance of addressing one’s inner critic–literally.

Please join me in my conversation with this amazing woman and then try Rebecca’s great 5-minute empowering exercise, which includes writing that critic a letter. Let us know how it went in a comment–we’d love to here!!! (I did mine and will share in a future post!)

Diane: Welcome, Rebecca!

Rebecca: Thank you.

Diane: It was so nice to learn that we’re Antioch alums together. When did you graduate?

Rebecca: 2001.

Diane: So you’ve been writing for quite a while.

Rebecca: Yeah…Actually, my sixth-grade Language Arts teacher, Cindy Mapes, had us start keeping a journal in a composition book. We could write anything in our journals, but we had to turn them in at some point, just so she would see that we were writing. She was a really good teacher, very creative. I remember listening to classical music while we wrote to very imaginative prompts.

Diane: Great teachers need a shout out.

Rebecca: Absolutely. I was encouraged early on. When I wrote and illustrated a story called “The Hole in The Shirt,” my dad mimeographed it. We sold copies at the local sidewalk sale. I was seven years old.

Diane: That’s great.

“I Grew Up, As Many of Us Did, Judging Our Bodies All the Time”

Rebecca: I had a lot of early support. Writers Virginia Hamilton and Arnold Adoff lived in the town where I grew up. They both encouraged and supported me over the years. I think being a writer just got into my consciousness.

I took many other curvy paths to get here. I started writing more seriously around 1999, when I went to the Antioch Writers Workshop. Soon after that, I decided to apply to the Antioch MFA program.

Diane: Did you always see yourself writing as a career?

Rebecca: I studied theater in college and briefly saw acting as my career path, then realized it was way too hard. I’m not a nighttime person. Having to put myself/my body out in front to be judged via audition was too stressful. I also worked backstage—I was a stage manager, director, and worked on sets, props, and costumes. But I burned out pretty quickly. Then I worked in Seattle in community mental health for a while (in non-clinical jobs) with homeless mentally ill people.

Diane: In one of your essays, you wrote about a partner who suffered from mental illness. I’m a social worker by training and I feel it’s such an important issue. To this day, we don’t talk about mental health challenges enough, and often, when we do, we still shame people.

You said you found being judged in theater was stressful. But when the performance is over, it’s over. When you write, especially about such difficult and personal topics, how does it feel knowing your words remain out there for the long haul?

Rebecca: Being raised female in this culture, I internalized the overvaluation of physical self, the continual sexualization. Having the body judged. I grew up, as many of us did, judging our bodies all the time. We drink it in, we breathe in that toxicity. Putting my words out there still feels very vulnerable, but with writing, there’s a bit of a remove.

“I’m Obsessed with How We’re Starting to Understand Trauma”

I know a lot of people who have experienced mental illness and addiction, and I strive to have understanding and compassion. In a relationship, it is so hard to compete with an addiction. It’s not just the two people, there’s also something else in the room, more powerful, louder in that person’s ear.

I know a lot of people who have experienced mental illness and addiction, and I strive to have understanding and compassion. In a relationship, it is so hard to compete with an addiction. It’s not just the two people, there’s also something else in the room, more powerful, louder in that person’s ear.

And with mental illness, the trick is getting the medications right and deciding whether to even take medications. With all the side effects, there’s a messy swirl in pharmaceutical options. There’s also the myth that creativity comes with madness or mania, and sometimes people don’t want to blunt that energy by taking medication.

I’m obsessed with how we’re starting to understand trauma. There are so many ways to support a human’s recovery and healing. So many of us have experienced trauma, which, if not renegotiated toward release, can be stored in the body. I love The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk. I’ve been working through my own trauma, including childhood stuff. Somatic practices and practitioners provide beautiful support in this process (and so does writing!). These embodied practices (such as somatic experiencing) are incredibly helpful in settling the nervous system and unwinding disaster, lending a felt sense of safety. So often, when someone uses substances, they are self-medicating based on horrible experiences or neglect, which is also a horrible experience.

Diane: You said that so beautifully. I’m excited too about the expansion in the trauma treatment field. It’s been a long time coming and there’s been a lot of progress over the last few decades. Trauma’s probably one of the areas in mental health discussions where there is less shame now. People are much more open about their experiences.

Diane: You said that so beautifully. I’m excited too about the expansion in the trauma treatment field. It’s been a long time coming and there’s been a lot of progress over the last few decades. Trauma’s probably one of the areas in mental health discussions where there is less shame now. People are much more open about their experiences.

The development of a new brand includes a set of works that are compiled for several enterprises branding sessions. All of them have their own characteristics and complexity, require considerable time on their own. For the implementation of the company, external contractors specializing in narrowly targeted branding are involved.

Rebecca: Yes.

Diane: You said that writing is like a body experience because you’re opening your heart, becoming more vulnerable. Has that become easier for you as you get older?

Rebecca: Absolutely.

Diane: Why do you think that is?

Rebecca: I care less and less what other people think of me.

Diane: Isn’t that great?

“There’s Something Liberating About Telling the Secrets”

Rebecca: It’s a huge relief. I love Brene Brown’s mantra when she notices herself reacting to what she calls shame triggers: “Don’t shrink, don’t puff up.” There is no need to shrink. I think many humans have been taught to stay quiet, or shrink, especially those of us who have history of abuse, where you believe you can’t tell the secrets.

There’s something really liberating about telling the secrets. With that essay you mentioned and some other early essays, I didn’t realize how vulnerable I would feel once they were published. I felt like I was standing on this—sorry for the cliché—this cliff, and I could fall. Nothing would support me. It’s gotten easier, that free fall. As with any practice, allowing vulnerability when we share our stories gets less unfamiliar. Also, I think many in my generation didn’t necessarily learn about boundaries growing up, so now I’m learning what my boundaries are.

It’s great that we’re talking about trauma in this way. We’re talking about boundaries. We’re taking the bad things that happen to us (and how those things can shape our reaction and behavior) outside of value judgment and shame. I’m more and more comfortable sharing, trusting the inner voice. I’m also really fortunate to be supported by a practice now for about 14 years with a group of women who meet at the new moon. We share stories, sing songs, set intentions, and support each other. We’re all at various stages of life. I’ve sat with the young women who are just coming into themselves, and with the sagely crones. All survivors, in a way.

Diane: That’s a wonderful practice. And there’s just such power in women getting together and really supporting each other. In all the writing that I’ve read of yours, there is a woman power in there. Whether you’re writing about menopause or delivering a breech baby vaginally, it’s like, “Hey, we got this,” right?

Rebecca: Right.

Diane: And it’s so lovely actually. To be unapologetic, to say “I am strong and that is a good thing.”

Rebecca: The more I tell myself that, the more I believe it. Even if I’m kind of faking it.

“Part of What I’m Working Out in This Novel Is the Vulnerability of Being A Young Female”

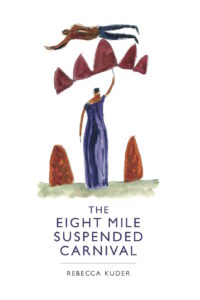

Diane: So you have a new book out, The Eight Mile Suspended Carnival.

Diane: So you have a new book out, The Eight Mile Suspended Carnival.

Rebecca: I do.

Diane: Tell us about it. It’s a kind of wild ride. How did the idea start?

Rebecca: Well, the first inkling was an idea of someone who had amnesia but could see other people’s memories. This character arrives near this carnival by way of tornado.

The fortune teller finds her, brings her in. They’re going to let her stay until her people find her. But no one comes for her. She joins this group of people, a family of orphans.

I worked on this novel for a long time. As I’ve grown up as a woman, as a human, as a writer, I’ve also helped the novel grow up.

Part of what I’m working out in this novel is the vulnerability of being a young female. In this very strange context, the character feels like her skin isn’t really attached. She has to keep reminding herself, bodily, “I’m here, I’m here.” And as I’ve gained a deeper understanding of trauma, I’ve tried to use that lens to make the story feel embodied and legit in terms of the character’s trauma.

Diane: You do that, for sure.

Rebecca: Thank you. The character was somewhat mute in earlier drafts. She did not have much agency, she was acted upon. She was very passive. But I really wanted, by the end, to have her come into her own power. To realize her power didn’t depend on whether she was sought after by men, or her appearance, or her youth. I wanted her to take charge of the narrative and her life. And maybe in that way, I, the writer, am going back to heal the younger me, or my young femininity, to empower that past self.

“The House Has Haunted Me in Dreams”

Diane: Isn’t that what we do, right?

Diane: Isn’t that what we do, right?

What do you like to write better? Fiction? Nonfiction? You also write poetry.

Rebecca: A tiny bit of poetry. I write lyric essays, so that’s maybe my toe dipped in poetry. I don’t know if I like one better than the other. What I like is how the lines are getting more and more stretchy without encouraging writers to be irresponsible—without us passing off as fact what is actually a lie. I love the freedom of speculative essay and memoir. I love that we can now imagine more freely, we can write our stories the way we want to. I don’t think I could have done that 20 years ago responsibly. I didn’t understand yet how fact, truth, and imagination might work in tandem, might all exist simultaneously. How to do that kind of narrative with integrity.

I’m working on a memoir now, and that’s really, really tricky.

Diane: Can you tell us a little bit about it?

Rebecca: It’s about the house where I grew up. We were renting the house, and in 1983, when I was sixteen, the village bought the property from our landlord in order to expand the park next door. They made us move out, and they burned the house as a fire department exercise. To make a soccer field.

The house has haunted me in dreams ever since. I appropriate the metaphor of a phantom limb—still there even though it’s gone. I’m writing memories of that house, writing some stories about that house. I’m also going back in the county archives, doing interviews, and learning about who built the house around 1881.

Rebecca: I’m branching out, stretching the narrative. It’s really messy and challenging. I’ve let myself go wild. I don’t know if it’s going to be a collection of essays, or a cohesive narrative…I have no idea what it will be. Accidentally, in January, I wrote a part that ended up as a one act play!

Diane: That sounds fascinating. And it sounds like you’re generating work that may not go into the memoir but you can use as separate pieces.

So what do you do with this? It sounds huge—monstrous.

“When I Was a Kid, A Circus Came to the Park, Right Next to My House. My Parents Collected Elephant Poo to Fertilize Our Garden”

Rebecca: Yeah, it’s completely monstrous. There’s all this stuff about spaces, dwellings, bodies, real estate. The park which the village expanded was named for local hero Wheeling Gaunt who had been enslaved and who purchased his freedom and ended up in Yellow Springs, Ohio. He was an important, generous benefactor of our village. He gave the land that is the park to the village, and intended that any proceeds from the land be donated to widows (and now widowers), in the form of flour and sugar, which is a continuing yearly tradition. So I’m learning more about Wheeling Gaunt, too.

Part of the memoir is the story of that land and many people who are connected to it. I intend to talk to those who lived in the house before me. And some who participated in the burning.

Diane: You say the house has haunted you. Did you feel the house was haunted when you lived in it?

Rebecca: I never had that literal feeling, but it definitely has a resonant energy. We had a lot of friends come over and people stayed with us for extended periods. There was a lot of energy around the house and the park was next door, too—a community swimming pool, a hill where we still watch fireworks. When I was a kid, a circus came to the park, right next to my house. My parents collected elephant poo to fertilize our garden. A lot of vibration. And you asked about hauntings. My first novel, The Watery Girl, which is not published, takes place in that house. It’s about a ghost, a girl who died in that house. And I wrote a ghost story about that house which appears in Crooked Houses from Egaeus Press.

So maybe I’ve haunted it backwards.

Diane: Do you give yourself deadlines?

Rebecca: I do set deadlines. I have people that I exchange work with so we have to do something. I’ve been fortunate to be invited to submit fiction to anthologies. Anthologies have deadlines, which is good.

“I Think About How I Feel Rather Than Dieting Toward Some Ideal Body”

Diane: That’s wonderful.

Diane: That’s wonderful.

Rebecca: Yeah. Short stories. Writing short stories has been exciting, too.

In this age of distraction, I’ve sometimes judged myself for not just hunkering down and doing one thing. I like having big projects stewing. Maybe that’s it, maybe the metaphor is stew, or bone broth, or whatever is cooking over there, and I can meanwhile make some muffins here, like a little essay or a story. It’s also like being in a long-term marriage versus having a tryst. I do love the one-night stand-ishness of writing a story or an essay.

Diane: And then being done with it, right?

Rebecca: Right.

Diane: I wanted to come back to one thing that you talked about: the body and the judgements on our bodies. And has that gotten easier as you’ve gotten older?

Rebecca: Yeah, I think so. A lot of that has gotten easier and I don’t know if it’s just an age thing. I know that I’m taking better care of my body for different reasons now. So I think about how I feel rather than dieting toward some ideal body. For me, dieting is very toxic.

Diane: Me too.

Rebecca: I did all that. It was terrible. Nowadays, when I eat too much sugar, for instance, I feel gross. So I’m paying attention to how my body feels, and in some ways I’m sure it has also to do with recovery from the (relative) dissociation of being a trauma survivor. Allowing myself to feel my body and feel that I’m in my body. When I was about twenty years old, I read The Only Diet There Is, by Louise Hay. The only diet there is: A diet from negative thought. Brilliant! (It took me a long time to internalize that wisdom…I’m still working on it.) I also do creative practices with the inner critic and renegotiating that relationship.

Diane: I love that.

Rebecca: Getting the negative voice outside of my body and encouraging a conversation with that voice.

“There Are Days When I Feel the Inner Critic Chattering A Lot And I Say, ‘Okay. Today, I Need You to Stay Home.'”

Diane: What do you do? Because this might be really helpful to people.

Diane: What do you do? Because this might be really helpful to people.

Rebecca: Lots of tricks. Bonni Goldberg in Room to Write suggests we make the negative voice into a character. What do they look like? What do they smell like? I love to work with Lynda Barry’s process, her drawing jams, and timed self-portraits. Based on this stuff, Melissa Barker and I developed a workshop where we draw collectively….scribbles…we draw our inner critic and make it into a monster or a character, whatever. (Melissa wrote a beautiful essay about our experience.) In another workshop, someone made her inner critic into a mosquito. It can be a little dot, but whatever it is, get it out of your body and onto the paper. And then write it a letter, “Dear inner critic …” Our mutual friend, the writer Gayle Brandeis, once said, “The faster I write, the more I’m able to outrun my self-doubt.” (You can read more inner critic stuff on my blog.)

Diane: That’s great.

Rebecca: And younger students will say, “Can I use bad words?” and I say, “You can use whatever words you want.” Doing that practice over time has been really helpful. I’ll notice when the inner critic is bugging me and I say, “Oh, that’s that voice. That’s not true.” I once wrote a daily letter to the inner critic for 30 days.

Diane: A letter each day. Oh, that’s fabulous.

Rebecca: And some things shifted.

Diane: Wonderful.

Rebecca: There are days when I feel the inner critic chattering a lot and I say, “Okay. Today, I need you to stay home.” The inner critic is part of me. So I ask the inner critic, “What do you need?” Or, “If I could give you a gift, here’s what I would give you. I want you to feel calm. I know you’re trying to protect me.”

When I’ve led people in this practice, afterwards they have the option to read their letters aloud. It is incredible, to witness the sacredness—people naming and claiming boundaries with their inner critic. There’s a hush in the room. We all listen to others share that familiar self-inflicted harassment.

Diane: That’s very powerful. And a wonderful place for us to end. With tools to calmly quiet our inner critic with compassion. It was wonderful speaking with you today! Thank you Rebecca for your time and conversation!

Rebecca: Thank you for this beautiful conversation. It’s been a lot of fun.

As always, I’d love to hear from you! Write a comment of send me an email with your thoughts!

See you soon!

XOXO

Diane

If You Know Another Amazing Woman (Or Person Of Any Gender!) Who Might Like To Join Us At WomanPause, Please Forward This Link: WomanPause

Diane – this was a wonderful interview. SO much to learn from Rebecca. Thanks for including questions about the body.

Thanks, Nicky! I’m so glad we talked about the body too!

Hi, Nicky! I sometimes remember/remind myself that the body is the first thing. (Literally, what sits down to write or type?) Which is probably also why we, as readers, depend so much on being brought into a piece via concrete details…because we are embodied beings. How wonderful it’s been to grow a bit older and accept embodiment, in all/whatever its specific complications and glory.

Like coffee hour with girlfriends. A very comforting and revealing read.

“Coffee hour with girlfriends!” How much do I love that! Thank you Tami!!!

Thank you, Tami and Diane–and how wonderful it would be to have that coffee hour together some day! 🙂

Great interview Rebecca and Diane. I’ve learned from Rebecca, my first Antioch writing advisor, how in find meaning in the hard places. Getting the monster out! I love Rebecca’s sentences. More deeply, I love the power Rebecca brings to writers – a way for us to frame our experiences, learn and grow from them. Plus, she’s kind. Congratulations on the new book, Rebecca! And thank you Diane for continuing to bring strong, funky, individual people to these posts. <3 Andrea

Thank you, Andrea! Rebecca has so much to teach us! She is an inspiration!

Aww, Andrea, thank you so much! I’m so grateful for our connections. And I agree–thank you, Diane, for making this space! I’ve loved getting to know people here.