Interview With Casey Mulligan Walsh

Casey Mulligan Walsh has not had it easy. She lost both parents when she was very young, her brother when she was 20, and then she experienced every parent’s worst nightmare–the loss of a child, her beloved son Eric. How to move on from such losses? “Moving on” may not be the right words, as wounds so deep never fully heal. But Casey has created a life of deep meaning in the face of all this loss. She embraces the beauty of holding both grief and joy, and she has found true belonging. I am grateful to Casey for speaking with me on Zoom shortly before Christmas and for sharing her story.

Diane: I’m so grateful that we’re talking today, because I admire you so much. I believe the first time I saw your work was in a Huffpost Personal article “This Is What No One Tells You About Losing A Child.”

For people who aren’t familiar with your story, can you tell us a little about it?

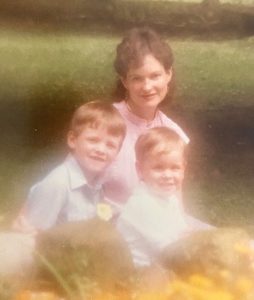

Casey: Yes. I’ve written a memoir and am now in the querying/submitting phase. As Vivian Gornick says, a book has both a situation and a story. The plot—the situation—is that my parents died 10 months apart when I was 11, then 12. I was sent from suburban New Jersey to upstate New York to live with my aunt’s family. My brother, who was seven years older than me, stayed in New Jersey, married, then moved south. He died at 27 of a heart attack, from the genetic cardiovascular disorder that runs in my family, which I also have.

“True Belonging Differs from Fitting In”

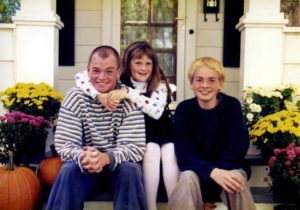

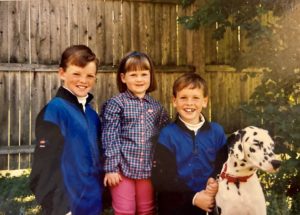

Losing my family so young, I set out on a search for belonging, though of course I couldn’t see that at the time. I left college early, married fairly young, and had three children. My husband’s family became my own. That marriage ended over 20 years later in a protracted, hostile divorce. During those difficult years, as I grappled with what I believed and how to find peace amid so much struggle, my oldest son died in a car accident.

Losing my family so young, I set out on a search for belonging, though of course I couldn’t see that at the time. I left college early, married fairly young, and had three children. My husband’s family became my own. That marriage ended over 20 years later in a protracted, hostile divorce. During those difficult years, as I grappled with what I believed and how to find peace amid so much struggle, my oldest son died in a car accident.

But my story isn’t only about death and loss.

The thread running through my story is the search for belonging and coming to understand how true belonging differs from fitting in. It’s also about finding meaning in the face of repeated loss and finding a way to live with the grief that never goes away but also with joy.

Diane: I’m so sorry for all your losses.

Casey: Thank you, Diane.

Diane: There’s something about a sudden loss that adds a different layer.

Casey: There is, because you just don’t have that time to prepare, make peace, or say goodbye.

Diane: And the loss of a child, I can’t even wrap my head, even a tiny bit, around that.

Casey: When I was young, people often asked how I’d gotten through the loss of my parents and my brother. I typically told them, “Somehow I survived those things, but if anything ever happens to one of my children, you can put me to bed and don’t expect me to get up again.” But when tragedy happens, it’s often very different from the way you’ve imagined it.

“I Was Worried Something Bad Would Happen, But I had No Way of Knowing What That Would Look Like”

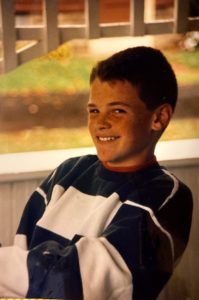

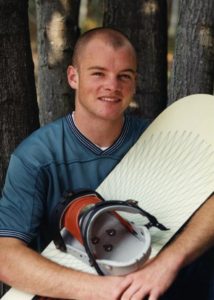

Eric was a gregarious, charismatic kid, but he, like a lot of teens and young adults, had difficulty transitioning through high school to life afterward. In addition to our divorce, a number of other stressors caused him to struggle in the years leading up to his death. Though he was facing these challenges, his accident was still a complete shock. I was worried something bad would happen, but I had no way of knowing what that would look like or when it might strike.

Eric was a gregarious, charismatic kid, but he, like a lot of teens and young adults, had difficulty transitioning through high school to life afterward. In addition to our divorce, a number of other stressors caused him to struggle in the years leading up to his death. Though he was facing these challenges, his accident was still a complete shock. I was worried something bad would happen, but I had no way of knowing what that would look like or when it might strike.

It’s been more than 23 years since his death, and all these years later I think of his passing as the combination of a long, slow decline–like you might experience through an illness or with kids who have addiction issues, which was not Eric’s story—and a sudden, tragic loss.

Diane: I always recommend that people read books and articles that the people I interview write, but I am going to stop just short of begging people to read your HuffPost piece—and “Still”.

“Still” is a one-sentence, urgent essay that takes the reader’s breath away, about that day in the hospital, in the ER.

Casey: That moment, really.

Diane: That moment, yes. Distilled. It’s incredibly powerful. And I just need to salute you for that piece of writing. It’s getting accolades all over the place, but I’m just adding one here.

Casey: That means so much to me, thank you.

Diane: I’d love for you to tell us a little bit about the wonderful things about Eric.

“The Other Side of That Outgoing Personality Was a Need for Air and Danger”

Casey: Oh my gosh, I’ll be happy to do that. He was my oldest, and I was only 24 when I had him. Having that first baby, I felt as if I had a family again. And from the time he was little, he was outgoing, an extrovert. I write in my memoir about how, even as a little guy in a high chair, we’d go out to dinner, and the couples at the tables around us would be paying more attention to him than to each other.

Casey: Oh my gosh, I’ll be happy to do that. He was my oldest, and I was only 24 when I had him. Having that first baby, I felt as if I had a family again. And from the time he was little, he was outgoing, an extrovert. I write in my memoir about how, even as a little guy in a high chair, we’d go out to dinner, and the couples at the tables around us would be paying more attention to him than to each other.

We lived in a very New England-y upstate New York village on the Vermont border. The school was basically in our back yard, and the big kids would walk down our village street, past our house, on the way home. From the time he was little, Eric knew them all, so one of them started to call him “Mayor.”

The woman who babysat for us used to say that Eric was one of the few kids she sat for all those years who never got to that teenage phase of being too cool to stop, say hi, and have a chat. But the other side of that outgoing personality was a need for air and danger. He had ADHD and was sensory-seeking and adventurous. He was drawn to water skiing and snowboarding. Even with soccer, it was all about going big.

One of the things that happens when you’re a risk-taker is that you get away with pushing up against danger over and over. Until the last time you take that risk, and then it’s too late.

“How We Choose to Think and React Shapes Who We Become”

Eric was not a big reader or writer, much to my chagrin. But he was very good at drafting, and he really would’ve loved that as a career. He did spend a semester at college for industrial drafting and design, but he was too untethered at that time to be successful. Then he enrolled in the Navy, but, sadly, a Naval career never came to be.

Eric was not a big reader or writer, much to my chagrin. But he was very good at drafting, and he really would’ve loved that as a career. He did spend a semester at college for industrial drafting and design, but he was too untethered at that time to be successful. Then he enrolled in the Navy, but, sadly, a Naval career never came to be.

Diane: Thank you for sharing who he was. I know with a horrific loss, people sometimes focus only on the horrific part.

You quote Carl Jung, “I am not what happens to me, I am who I choose to become.” This feels so true. I remember the night my husband died, I said to myself, “I am going to grow from this because this pain hurts too much. It can’t be wasted pain. It has to serve some purpose.”

Casey: That’s a wonderful way to put it.

There’d been a lot of trauma and difficulty in our family in the year and a half to two years leading up to Eric’s death. So I’d had this deep dive into changing my perspective on how I saw the world. I embraced the belief that we really are all connected, even if we’re separated physically, though we put up walls thinking that will protect us. That we act out of love or fear, and that what we give, we receive, but not in a trite way. It’s more about the notion that how we choose to think and react shapes who we become. So when Eric died, I had, like you, a lot of those unexpectedly lucid thoughts.

“Yes, I’m Going to Wear This to Bury My Son. I’m Also Going to Have Moments of Joy in This Dress.”

People have said, “You couldn’t have been that together, to think those things right away, in the middle of such tragedy.” But for me, it had to do with everything I’d been through leading up to that day, all the things I’d already absorbed.

People have said, “You couldn’t have been that together, to think those things right away, in the middle of such tragedy.” But for me, it had to do with everything I’d been through leading up to that day, all the things I’d already absorbed.

I’ve written a piece about this, actually, that I haven’t placed yet. Eric died on a Saturday, and I realized I had to find a dress for the memorial the following weekend. At the store, when I finally put on the dress that felt right, I looked in the mirror and thought, Yes, I’m going to wear this to bury my son. I’m also going to have moments of joy in this dress. I’ve been warned that this may not be believable to some readers, that many won’t relate to having this perspective so soon after a child’s death. Certainly I was grieving, crying and deeply sad, but I think when you have an innate belief system, it does come through for you, even in the worst times.

Diane: Absolutely. You talk about this in another piece, in The Good Men Project. You can hold both—grief and joy.

Casey: Yes, I believe that so strongly.

Diane: I totally believe that the joys feel that much sweeter when you’ve experienced that level of pain.

Casey: It’s true. Absolutely.

Diane: I LOVE your website —and hey everyone, she created it herself! You include a lot of inspiring quotes. But these are your words: “Grief is not linear. It’s here, then gone, dormant then wild.”

Sometimes, when you have a great loss, it feels like it happened in another lifetime, and then, a moment later, like it happened yesterday.

“I Sometimes Picture My Life As a Timeline, with a Big Black Slash Dividing the ‘Before’… and the ‘After’”

Casey: Yes. I so relate to the “other lifetime” feeling, especially in regard to my parents and my brother. I sometimes picture my life as a timeline, with a big black slash dividing the “before”–the years when my parents were alive—and the “after,” when I moved, alone, to live with another family.

Casey: Yes. I so relate to the “other lifetime” feeling, especially in regard to my parents and my brother. I sometimes picture my life as a timeline, with a big black slash dividing the “before”–the years when my parents were alive—and the “after,” when I moved, alone, to live with another family.

It wasn’t until I was in my 30s that I really allowed myself to connect to the fact that I actually did have a family, that there were people I resembled. I was used to being solo. So there’s definitely another life feeling to that.

Even 10 years after Eric died, I’d sometimes come into the house, look at his picture, and think, No, that didn’t really happen. There have been times in my life when I’ve thought, What’s wrong with me? I seem to be completely at peace with this. And a parent’s worst fear: Maybe I didn’t love him enough. Then I read or watch something evocative, listen to one song, and I’m a puddle.

Diane: Those triggers, right out of nowhere.

Casey: Music, oh my God, music especially.

Diane: Music is really important in your life.

Casey: It is. My husband sometimes comes in to find me teary—even now–and says, “Oh God, you’re not listening to that song again, are you?”

I’ve always loved music. And then, around the time just after Eric died, in the early 2000s, I was introduced to some regional singer-songwriters, Dar Williams among them. There’s something about her literary lyrics and music and voice that just cut right to your heart.

“The Real Thread Is the Search for Belonging, Finding Meaning in Loss, and Living a Life of Grief and Joy”

In my essay, “The Beautiful Game,” published in The Under Review, I wrote about seeing Into The Woods right after Eric died. There are lyrics in Sondheim’s play about how children go from something you love to something you lose. It was painful to watch, but there are times that something gets right to the heart of how you feel, and maybe you have a good cry just when you need one.

In my essay, “The Beautiful Game,” published in The Under Review, I wrote about seeing Into The Woods right after Eric died. There are lyrics in Sondheim’s play about how children go from something you love to something you lose. It was painful to watch, but there are times that something gets right to the heart of how you feel, and maybe you have a good cry just when you need one.

Diane: It’s like with sad love songs. People gravitate to them, because they speak to our experience.

Casey: I think so, yes.

Diane: So tell us more about your book. I love the title.

Casey: Thanks! The title is The Full Catastrophe. I think all of us who write books agonize over subtitles. Not to offend anyone who’s used something along these lines, but I was trying to steer away from a subtitle like “a memoir of love and loss,” or anything about a journey home, which my friends all said sounded too much like Lassie. So the subtitle now, which I actually like because it illustrates the double meaning of The Full Catastrophe, is All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared.

Diane: That’s beautiful.

Casey: Thank you.

Going back to Vivian Gornick and the situation and the story, the situation is obvious: I’ve had a lifetime of repeated loss.

My husband used to ask me, “But what is the book about?” Essentially, what he was asking is, “What’s the story?” I’d say, “It’s about resilience after a life of relentless loss and trauma.” “Yeah, but what is it really about?” he’d press. And he was right, it’s deeper than that. At one point in the process, I understood the real thread is the search for belonging, finding meaning in loss, and living a life of grief and joy.

“I Tried Really Hard to Be a Chameleon, Twist Myself into Whatever I Thought People Wanted Me to Be”

I didn’t simply survive all those losses, they shaped me into someone whose number one goal was to find belonging. We often don’t do that in the right way, at least at first. I worked hard to stay under the radar, below the level of reproach. To not draw any negative attention. To prove my worth. I tried really hard to be a chameleon, twist myself into whatever I thought people wanted me to be. But in the end, belonging requires you to be fully yourself.

Diane: Absolutely.

Casey: It’s funny, we were talking before we recorded about how I built my website through sheer determination, which has gotten me through many roadblocks in life. But determination is not always a positive quality. Sometimes, you can be so determined that you don’t know when to let go of something. That’s been true for me.

Diane: I think that’s true for many of us.

Just yesterday, I was talking about a short story I read. I don’t remember which one, but a character said there’s no word in the English language for having lost a child. And then, this morning, I read the same thing on your website!

We have the word “orphan,” we have the word “widow,” but nothing for a parent who lost a child.

Language really reflects our culture. We don’t want to look at that, we don’t want to say it, we don’t want to hear about it. How was that all for you? It’s hard for people to hear about experiences like yours. Did people shut you out?

“People Don’t Want to Talk about Death, Or They Don’t Know What to Say”

Casey: Yes, it is hard.

Casey: Yes, it is hard.

Eric died on June 12th. I was a speech-language pathologist at a public school, so I didn’t go back to finish that school year. What that meant was that the first real reentry to my job was almost three months later. It felt as if it was old news by then, business as usual. Very few people said anything to me, and that was hard.

People don’t want to talk about death, or they don’t know what to say.

Diane: They don’t know how.

Casey: Maybe it’s the circles I travel in now, because I write about grief, but I feel like most of us know the big no-no’s: “He’s in a better place,” “At least you have other children,” and all of that. Most of us don’t say these things anymore.

I think the best thing you can say to someone, even years later, is “Tell me about them.” That’s such a gift to those who grieve. And when the loss is immediate, I think, “I’m so sorry you’re going through this. I’d do anything to change it if I could,” is about the most real thing you can say.

Diane: So true, Casey.

You also do some work around heart issues …

Casey: Yes, my husband and I are advocates for awareness for The Family Heart Foundation. FH– familial hypercholesterolemia—is the genetic form of high cholesterol. The LDL—the “bad cholesterol”– is the number that’s most important. For the general population, LDL should be under 100. FH is suspected when LDL is over 190, no amount of lifestyle changes—changes in diet and exercise–will budge it, and there’s a family history of early heart events.

“One in 250 People Have FH. It’s As Common As Type I Diabetes, But Few Have Heard of It”

My father died in 1966, when few people were diagnosed. My brother died of a heart attack at 27 in 1975, and he didn’t know he had this condition, either, but an autopsy revealed significant atherosclerosis. I was diagnosed a year later. When I wrote a first-person account of living with FH for an American Heart Association Journal a couple of years ago, the geneticist/cardiologist who edited the publication was amazed I’d had an accurate diagnosis in a small upstate New York town in 1976, when so many people remain undiagnosed today. I also write about FH in a monthly WebMD patient perspective blog.

My father died in 1966, when few people were diagnosed. My brother died of a heart attack at 27 in 1975, and he didn’t know he had this condition, either, but an autopsy revealed significant atherosclerosis. I was diagnosed a year later. When I wrote a first-person account of living with FH for an American Heart Association Journal a couple of years ago, the geneticist/cardiologist who edited the publication was amazed I’d had an accurate diagnosis in a small upstate New York town in 1976, when so many people remain undiagnosed today. I also write about FH in a monthly WebMD patient perspective blog.

One in 250 people have FH. It’s as common as type I diabetes, but few have heard of it. When the Foundation was started, 1% of the people in the country who had it were diagnosed. Now , approximately 30% are. But that means 70% of the people who have it still don’t know. I suspect a lot of people know they have high cholesterol, but have not received a diagnosis of FH.

Many physicians are not well-versed in FH or don’t diagnose an individual’s high cholesterol as genetic. Because of this, one of our current initiatives is “Runs in the family is not a diagnosis.” FH is an autosomal dominant gene, which means that if an individual has FH, their siblings, parents, and children each have a 50% chance of having it. So once someone is diagnosed, there’s an ethical responsibility to make sure family members are tested.

“My Entire Life, I Assumed I’d Die Young”

Those of us with FH have had plaque-developing levels of high LDL since in utero. This isn’t something that happened as we got older. This makes it even more important that LDL levels be brought even lower than the benchmark for the typical population.

Those of us with FH have had plaque-developing levels of high LDL since in utero. This isn’t something that happened as we got older. This makes it even more important that LDL levels be brought even lower than the benchmark for the typical population.

Diane: That’s wild.

Casey: So there are three-year-olds and five-year-olds who already have plaque developing. The good news is the recent advent of the PCSK9 inhibitors, injectable medications. They’re miracles. My LDL now hovers around 40.

My entire life, I assumed I’d die young. My whole family already had. But with these new medications, there’s a possibility of halting further plaque development and possibly reversing the damage that’s already been done.

Eric had FH. The irony, of course, is that I always worried he might die young of a heart attack. My daughter has it, and one of my granddaughters has it as well.

Diane: Tell us a little bit about grandchildren?

Casey: I met my husband not long after September 11th, in 2001. We got married the following September, so we’ve been married 20 years. Between us, we have 10 grandkids–six boys and four girls—ages 4 to 18.

Diane: Do you do the big family thing, get everyone all together?

Casey: Yes and no. We did a lot more of that before the pandemic. I have to say, back to the concept of letting go of control, before the pandemic I was much more devoted to the idea that everybody should all be here together at the same time and threw myself into orchestrating all of that. I’ve become much more accepting of gathering however and whenever it happens. But we see them all, and we’re close to them all.

“As Long As We’re Here, Our Story’s Not Over”

The idea of The Full Catastrophe–not everyone may know it’s from the movie Zorba The Greek. Boss asks Zorba, “Are you married?” and he says, “Am I not a man? Of course I’ve been married. Wife, house, kids, everything…the full catastrophe!”

That’s what I wanted–the worries and the bills and the joys–all of it. And I got it. But then, through the divorce and Eric’s death, it felt as if I’d lost it all, as if I’d gotten the literal full catastrophe instead. In recent years, we’d have holidays here with all the kids and grandkids, and it was chaotic and fun. There it is, I’d think. The full catastrophe I’ve searched for.

Diane: That’s wonderful. Yay. That’s your ending. Happy ending to the book. Not the happy ending. We’re not ended, right?

Casey: As Orson Welles said, “If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.” As long as we’re here, our story’s not over.

Diane: What a wonderful place to end our interview. Thanks so much Casey! Looking forward to your book, The Full Catastrophe!

As always, I’d love to hear from you. Please write a comment or send me an email.

See you soon!

XOXOXO

Diane

I can only hope that one day I can hold joy along with grief. Losing my 21-year old son just 12 weeks ago, it’s hard to imagine how I will ever smile again. I don’t know how long it will take for me to reach Casey’s point in her healing, but her story gives me some hope. Thank you Diane for publishing this story. Unfortunately, we will all go through loss and grief if we live long enough. It’s important to hear that we will survive through it.

Sending you tons of love and hugs, Denise. You will smile again. And hold joy along with grief. XO

Denise, I’m so, so sorry to hear of your loss, so recently. I can put myself right back there and feel all the feelings right along with you. I’m gratified you can find a glimmer of hope in my story. Give yourself all the time and compassion you need. Sending lots of love.

Beautifully heartbreaking story, Diane!! Such a gorgeous interview!!

Thanks Janet! Casey is amazing!

Thank you so much, Janet, for reading and for your comment.

Such a powerful interview. Everything in it, from both of you, resonates with wisdom and the both/and-ness of life. Beautiful, painful, and memorable. Thank you.

Thank you so much, Alison. Casey is an amazing woman–it was a great pleasure to speak with her. Love the “both/and-ness of life.” What a true and wonderful way to put it. Xo

The both-ness of life. I love that. And yes, the beauty and pain live side by side for all of us I think, all the time, whether we’ve had losses through death or not. I’m grateful for readers like you who let us know what resonates.

Great interview, Diane. I love Casey’s pieces that you linked to.

Thanks, Isidra! Aren’t they wonderful–I’ve read them several times and they still haunt me.

Isidra! Thank you so much for taking the time to read and comment here, and for reading some of my other work. The rest can be found at my website. Grateful for your support.

What a fantastic interview. I’ve gotten to know Casey over the past two years, first online, and then, happily, IRL. But if I hadn’t had the opportunity, I’d feel like I know Casey after reading this. No matter how many times I’ve read her amazing flash piece, Still, I’m (still) moved to tears with every reading. I think of a line I once heard, “There can be no greater art, than walking with a broken heart.”

Oh Eileen! I love that quote! Thank you so much for your beautiful comment. I “still” am moved too–everytime I read that piece!

Dear, dear Eileen. Thank you as always for your support in every way. And I love that quote. We’ve walked a similar yet very different path. I’m grateful we can spend even a small part of it together.

Wow! “But in the end, belonging requires you to be fully yourself.” This really resonated with me, and I know who can love me as me.

I’ve experienced great loss as well, and Casey’s words—as were yours—were liberating. I felt validated in all the ways I’ve felt: both joy and grief.

Thank you, Diane, for bringing these amazing women to us. I am forever grateful.

Oh, Teri! Thank you so much for your comment! I am so grateful that Casey’s words resonated and validated. I am so honored to bring amazing women to WomanPause readers–it is a joy and a privilege. Thanks so very much for helping to make this community the supportive space I’ve always hoped it would be! XO

Teri, thank you. so much for reading and taking the time to comment. Those of us who have experienced significant loss have a bond, and when I find kindred spirits, others who validate my own path, I’ve found it to be such a gift. It means so much to me to know you’ve found that here.