Interview With Eileen Vorbach Collins

Eileen Vorbach Collins is an amazing woman, who has survived every parent’s nightmare: her beautiful teenaged daughter Lydia died by suicide. While Lydia has been gone for over 20 years, grief remains. Although grief looks and expresses itself differently, the loss will always weigh on Eileen’s heart.

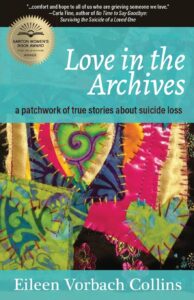

Eileen has written a powerful and heartbreakingly beautiful memoir called Love in the Archives: a patchwork of true stories about suicide loss. Here’s a review I wrote about it that was recently published in The Colorado Review.

Here’s Eileen reading her stunning flash essay Howl and Whisper, published in Emerge Literary Journal.

And here’s a shorter version of our interview published in Mom Egg Review. I hope you will read this longer one, as Eileen shares so much wisdom and love.

Diane: Welcome, Eileen! I’m so excited to be speaking with you. Congratulations on your book Love in the Archives. I loved it. It’s wonderful though it’s not an easy book to read. Readers may need to put Archives down here and there, but they won’t put it down for long because it beckons. Can you share what the book’s about?

Eileen: I appreciate that you say it’s not an easy book to read. It was certainly not an easy book to write. I made it into a collection of essays because I needed it to be put-downable. I needed each one of those essays to stand on its own because who could read a book like that from cover to cover?

The book is primarily about my daughter Lydia who died by suicide when she was 15.

I had written and published a few essays, thinking I would one day put them in a book. When I started querying, I was told a book of essays would never sell, that I needed to make it a traditional memoir with an arc. One publisher told me, “I will help you do that. We can work on this together.” I actually gave that a try but decided it was not what I wanted to do.

My book needed to be bits and pieces. There is a narrative arc, but you might have to trip over it to notice. It’s not a chronological story. It moves around a bit, not unlike grief. I did what everybody does, taking the parts and putting them out on the floor, rearranging them to make little visual things of where each chapter should go. I did that repeatedly and finally just said, “Okay, I’m done. It either gets published or it doesn’t, but I’ve got to be done with it.” And I’m happy that it found a home.

“I Wanted to Show All Sides of My Quirky Brilliant Daughter”

Diane: Me too. There are so many different types of essays in here, which is really interesting.

Diane: Me too. There are so many different types of essays in here, which is really interesting.

Eileen: A lot are epistolary pieces. That’s just the way I think when I’m writing, because I talk to my daughter all the time in my head and sometimes out loud. I’m really writing a lot of it to her and to my son, and because it’s been more than 20 years since Lydia died, many of the people I know now, and many of my closest friends, never met her.

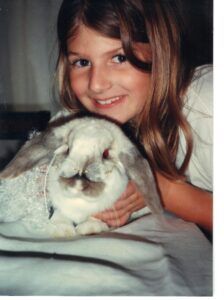

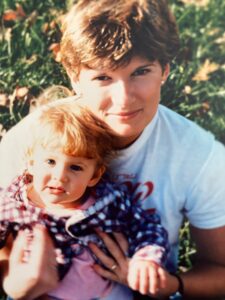

So, it was a way to introduce her to them. When you lose a child, we tend to canonize them. They were just the smartest, the most wonderful, the most beautiful. And yeah, they were, but then they had their other side as well. I wanted to show all sides of my quirky brilliant daughter because that’s who she was. And so I never really sat down and said, “Okay, I’m going to write a braided essay or I’m going to write an epistolary essay.” It just happened.

“She Was Always Bringing Home Characters”

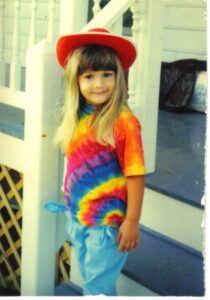

Diane: Can you tell us about Lydia?

Eileen: Yeah. Lydia had the greatest sense of humor, and she was just this outgoing kid. We could go to the beach and she would meet a new best friend and want to bring him them home for a sleepover. And that best friend could be a 60-year-old man that she met in the water, or a three-year-old when she was 10. She just didn’t have that kind of, “Oh, I’m only going to look for people who look like me.” She was always bringing home characters. Some of the characters I wish she hadn’t brought home.

We would fight about, “No, you can’t go to their house, but they can come here because I don’t know who they are or where they live.” Once she hit adolescence, there were a lot of battles. But prior to that, she was just the most delightful, outgoing, friendly, smart kid.

She was hit by a car when she was nine years old in front of the house and had serious injuries, limb threatening injuries, so she had multiple surgeries and was in a wheelchair for off and on for a couple of years. A lot of pain. I’ve always wondered how much the trauma of that had to do with her later mental health issues. But those are the things we’ll never know.

“A Lot of People Want to Find a Why to Blame”

Diane: I so feel that. I mentioned to you, and most of my readers know, that my first husband died in a car accident. It’s a different layer of trauma when it’s a sudden death. I’m not saying worse or better, it’s just different. It adds a different texture. And even with something like that, I would say, “Okay, it was a rainy night. Well, what if he had driven more slowly or been in a different car?” Because his car, it was rear wheel drive.

Diane: I so feel that. I mentioned to you, and most of my readers know, that my first husband died in a car accident. It’s a different layer of trauma when it’s a sudden death. I’m not saying worse or better, it’s just different. It adds a different texture. And even with something like that, I would say, “Okay, it was a rainy night. Well, what if he had driven more slowly or been in a different car?” Because his car, it was rear wheel drive.

So many “what ifs” or “why” questions. In the preface, you wrote we’ll never know why. Why is a really bad question. It’s self-punishing, I think. And I think in the case when someone dies by suicide, there are so many people outside asking why.

You asked why too.

Eileen: For a long, long time.

Diane: How did you get beyond the why and what was that like? Did people ask you why directly?

Eileen: People still ask me why. Quite frankly, it pisses me off.

Diane: I don’t blame you.

Eileen: Because I want to say, “If I knew, I would’ve stopped it.”

Diane: That’s right.

Eileen: And although as a parent, I asked myself that, and still to this day, I’ll think, “Boy, if we had moved out of the city and lived in a rural area …” but then I know people who live in rural areas whose children died by suicide.

A lot of people want to find a why to blame. “It was because the juvenile justice system didn’t do their job or because the evil girlfriend dumped him,” but millions of other people got dumped by a partner. So that’s not the why. Can’t help but look for it though.

“I’ll Always Wonder What I Might Have Done Differently. Done Better”

There’s always that piece when you think back at a sharp word or an argument that you had and you beat yourself up about it, full of recrimination. “How could I have been a better parent?” My son helps me through these periods. He’ll say, “Mom, I remember when we did this, and this was a great time.” So that’s really helpful.

There’s always that piece when you think back at a sharp word or an argument that you had and you beat yourself up about it, full of recrimination. “How could I have been a better parent?” My son helps me through these periods. He’ll say, “Mom, I remember when we did this, and this was a great time.” So that’s really helpful.

Diane: In the book you said you thought maybe Lydia was just hitting adolescence a little earlier, but she had depression and often, especially with younger people, depression displays as anger. She was rebellious, quite rebellious sometimes.

Eileen: I wrote a piece about Lydia being bullied at summer camp. (Here’s the essay published in Today.) She never wanted to go in the first place. When we get there, she’s in a cabin with some divas, and Lydia was never the diva. It was a period of time where she had decided she was gay. And so she wrote about this and about a girl that she had a crush on. She journaled all the time and kept the journal under her mattress. The girls in that cabin waited until she was out and read it. Then they called her “lesbo” and “dyke” and all these things.

I told her, “We don’t have to put up with this. We can leave tomorrow.” But she didn’t want to. She said,

“I’m not going to let them ruin this for me.” I was proud of her.

After that article went to print in TODAY it wound up on Yahoo.com. I read some of the comments. They were all so critical: “It’s a mother’s job to protect her child.” “I would’ve left right away.” “I would have done this. I would’ve done that. Why didn’t she do this?” I got the sense that many of the comments were from people who’d just read the title of the article. Still, the comments stung because I’ll always wonder what I might have done differently. Done better.

“She Just Needed to Be Who She Was”

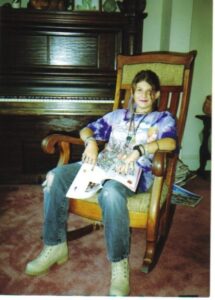

Should I have been a more strict parent? I was a very permissive parent in a lot of ways. If I showed you a picture of Lydia’s bedroom, you might wonder “Why did you let her do that?” Or “Why did you let her shave her head?” Or “Why did you let her dye her hair?” Back then it wasn’t as common as it is now.

But I thought, “These are things that she should be able to do.” So I didn’t say, “No, you have to have frilly pink curtains. You can’t have all these weird things in your room.” She had mannequin parts and things hanging from the ceiling. Her grandfather brought in the curator of the American Visionary Art Museum to see her room.

There was a certain artistic bizarreness about this kid. I could have threatened her with any punishment or any kind of, “I will take this away.” It wouldn’t have mattered. She just needed to be who she was. I could have said, “You will never leave the house again until you’re 18,” and she would’ve climbed out the window. And so, as a parent, you do what you can do.

Diane: Until you have a child who is, let’s call it “strong-willed,” you’ll not understand. Have people told you, “Well, just tell her no”? It can be infuriating.

Eileen: Yes. Or “Take away her TV privileges.” She never watched television. She had a sign on her guitar case that said, “Kill your TV.” There was nothing I could take away from her that would have made a difference.

“Some of the Last Words She Said to Me Were, ‘I Love You, Mom’”

Diane: A lot of kids who have this real strong will about them don’t care about consequences. They’re going to do what they’re going to do. And sometimes it serves them really well in the world and other times not. When you have a really creative kid who isn’t peer-pressure motivated or motivated by the same things that many people are, it’s really, really a challenge to find a way to parent. Besides, everybody makes parenting mistakes. But there’s a part of us, I think as mothers, that doesn’t allow ourselves grace.

Diane: A lot of kids who have this real strong will about them don’t care about consequences. They’re going to do what they’re going to do. And sometimes it serves them really well in the world and other times not. When you have a really creative kid who isn’t peer-pressure motivated or motivated by the same things that many people are, it’s really, really a challenge to find a way to parent. Besides, everybody makes parenting mistakes. But there’s a part of us, I think as mothers, that doesn’t allow ourselves grace.

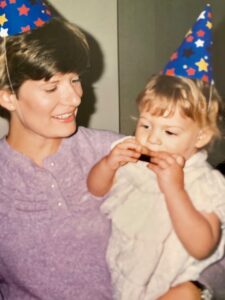

Eileen: What breaks my heart about this whole thing is that how close Lydia and I were up until we weren’t, and even some moments up until the day she died, some of the last words she said to me, were “I love you, mom.”

Diane: I’m so grateful for that.

Lydia was so creative. In addition to visual art, she also wrote and was really well-read. She played the flute, too, right?

Eileen: Yeah. She gave up the flute for a year or more. She was just depressed and she wasn’t playing at all. And then one day she said, “I want to take flute lessons.” So, I was all over that, “I’ll find you someone.” And we found a great teacher, someone Lydia admired, who said early on, “I want you to practice and apply. You won’t get in this year, but you want to start practicing and applying for the Maryland Youth Orchestra.”

“I Thought, We Were Over the Hump”

And right away she got into the Maryland Youth Orchestra, but she couldn’t stand to fail at anything, so she would practice and practice and practice. Before she died, she’d applied to a summer music program with a flute intensive. She was excited about maybe getting into that. I thought, we are were over the hump and doing really well. And I stopped my parental surveillance. Pretty much stopped snooping, stopped worrying because I thought things were going so well.

And right away she got into the Maryland Youth Orchestra, but she couldn’t stand to fail at anything, so she would practice and practice and practice. Before she died, she’d applied to a summer music program with a flute intensive. She was excited about maybe getting into that. I thought, we are were over the hump and doing really well. And I stopped my parental surveillance. Pretty much stopped snooping, stopped worrying because I thought things were going so well.

Diane: They can really keep things from us. No matter what you did, it wouldn’t have made the difference.

Eileen: Well, afterwards, I read her journals. She had never stopped thinking about death. There’s another woman I know whose daughter was similarly bright and creative and talented but who never showed any of the signs at all. She was, I think, valedictorian of her class. She was ready to go to college on a great scholarship, and she killed herself right after high school graduation. They were shocked when they read her journals. This bright and brilliant 18-year-old had long been obsessed with the idea of dying.

Diane: I mean, what do you say to that?

Eileen: That’s one of the things that bothers me so much about the whole idea of suicide prevention. While it’s critically important work, preventing suicide, I heard a licensed therapist say, not that long ago, “All suicide is preventable.” And it bothers the hell out of me because these parents had no idea. So how was that preventable? And with Lydia, right before she died, there’d been some issues and I was not letting her out of my sight that weekend.

She Wasn’t Out of My Sight for More Than Ten Minutes”

She was angry about that, and she knew the key words “contract for safety.” Still, I wouldn’t leave her alone that night. But while she was in the kitchen, I took a quick shower. She wasn’t out of my sight for more than ten minutes when she ended her life. She must have been planning it all day, despite her repeated assurances that she was okay.

She was angry about that, and she knew the key words “contract for safety.” Still, I wouldn’t leave her alone that night. But while she was in the kitchen, I took a quick shower. She wasn’t out of my sight for more than ten minutes when she ended her life. She must have been planning it all day, despite her repeated assurances that she was okay.

Diane: That’s really the thing when people are so determined to do something, and they’re determined people by nature. They do what they set out to do.

There’s so much in this book that the reader feels viscerally. At least it was that way for me, and I’m sure I’m not alone. I felt my own body gasp, my own heart break. But there are also places where I laughed and others where I just appreciated the beauty. Your language is lyrical and lovely. You write about the natural world and about marital struggles and religion. We are in good hands with you as a writer. And we do learn about Lydia. We learn who she is.

I think all that would’ve been enough. Suicide is the second cause of death for adolescents in this country, so a book that tackles the subject so honestly and openly is a necessary addition to that literature. But what stands out for me about this book, because I was a psychotherapist for years, is how the psychiatric field is so backwards when it comes to dealing with grief. You went to a therapist. Oh, how I wish you had had a better therapist. Can you want to tell us about her? What that was like? It blows me away.

“I Didn’t Need Her to Tear Her Clothing and Roll Around on the Floor and Wail, But I Needed Her to Look Sad, to Mirror My Sadness”

Eileen: She was highly recommended by a friend, pretty much said, “You’ve got to go to this person. You need this.” And so I thought, “I need this. I’ll go to this person.” And I just was so disappointed. She did not really engage with me at all. And I understand because my graduate degree is in pastoral care. I know that reasoning behind it. I suppose she thought she was being a listening presence. But she was really absent. I wanted someone that would listen and respond. I didn’t know, does she have earbuds and she’s really listening to some podcasts, or is she listening to me? When I talked to her about Lydia, I wanted to see some emotion from her. I didn’t need her to tear her clothing and roll around on the floor and wail, but I needed her to look sad, to mirror my sadness.

Diane: To be a human being, for God’s sake. You didn’t get any human response.

Eileen: I did not. When Dr. Jeffries read my book and said in his blurb this is a book that should be available to practitioners as well as people who are grieving, it validated that feeling for me that no, this is not the proper way to deal with someone who’s grieving.

Diane: It is not. It is so not. And I say that as a human being and as a former therapist. I don’t know how anyone could sit in a room with you and not feel moved and not respond as a human being. That wouldn’t be unprofessional. That is professional. We’re humans. So, that whole thing just blew me away.

And also, the parameters we place, these timelines for grief make me crazy. And pathologizing grief? Maybe if you never get out of bed again, that’s something that needs treatment because we want people to be able to get out of bed. But you went to work, you lived your life, you carried on. Maybe it’s not “moving on.” You don’t want to sever ties with your loved one. Why should you?

“It’s Not Something That You Can Cure Unless You’re a Resurrectionist and Bring Loved Ones Back”

Eileen: When I went to graduate school for pastoral care, I wrote my thesis on maintaining ties with our dead ones. And then 20 years later, we’re getting Prolonged Grief Disorder added to the DSM. I remember, as you do, it wasn’t that long ago that homosexuality was in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a diagnosis, something to be cured. I predict that within the next 10 or 20 years, they’re going to have sufficient pushback to reexamine this diagnosis as well.

Eileen: When I went to graduate school for pastoral care, I wrote my thesis on maintaining ties with our dead ones. And then 20 years later, we’re getting Prolonged Grief Disorder added to the DSM. I remember, as you do, it wasn’t that long ago that homosexuality was in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a diagnosis, something to be cured. I predict that within the next 10 or 20 years, they’re going to have sufficient pushback to reexamine this diagnosis as well.

Diane: I sure hope so.

Eileen: Although I see so many people writing articles—they’re all over the place in the big journals—that now there’s help for people who are grieving long-term. What’s the help? They’ve given it a name and stuck it in the book. That doesn’t mean we have greater access to care. It doesn’t mean that practitioners have learned anything. All it means is they’ve given it a name so that we can get insurance reimbursement under that code. I don’t get it. I don’t get how it happened, and I don’t know how this stuff happens, but everybody falls right in line for it.

Diane: I think it’s because grieving people make others uncomfortable, and people don’t like being uncomfortable. But like you said in your book, there’s no cure.

Eileen: There is no treatment for this. It’s not something that you can cure unless you’re a resurrectionist and bring loved ones back. I know there are people who have delved into the depths of despair and stay in that mired state. I get that. But that’s a whole different ballgame. Professionals haven’t given enough distinction between that thing, which I would say is pathological.

What I see is this split. There are so many people who have lost a loved one, who are just appalled by this diagnosis. And there are others who say, “Oh, now I have a diagnosis. So now they can fix me,” and believing that.

(Here’s a chapter of Eileen’s book about Prolonged Grief Disorder that was published in Alliance of Hope for suicide loss survivors.)

“I’ve Written Essays Since the Book, and I Probably Will Continue to Because It’s What I Do”

Diane: There’s nothing that needs to be fixed. I was going to say there’s nothing broken, but that may not be true. We’re all broken in different places and in different ways, and to paraphrase Leonard Cohen, that’s where the light shines through.

You wrote in the preface that you thought writing might help you release some of this grief, but you found there was always a full, new supply waiting. I have found that sometimes writing the really hard stuff can feel healing. And at other times you still feel really down after you finish writing. Has anything shifted for you in your grief process after completing the collection?

Eileen: I think it has. I think it’s given me this sense of, “Okay, this part I can put away.” I’ve written essays since the book, and I probably will continue to because it’s what I do, but now, “Okay, this part I can be done with.” Because writing a book is hard work. I’m satisfied, quite satisfied with the feedback I’ve gotten from people who’ve read it. And I feel good about it. (Here’s an essay Eileen wrote after the book. It was published in Dorothy Parker’s Ashes.)

“I Never Wanted to Write the Damn Book. I Never Wanted to Have This Thing to Write About”

You know what’s hard though? You have to do a certain amount of shameless self-promotion when you write a book, or nobody will ever see it. So when you do some of that and you post a snippet of a review that you were thrilled by, and you get comments like, “Oh, congratulations. Oh, I’m so happy for you.” That feels so weird. It is difficult to explain. I want people to read my book, but I don’t want all these happy congratulations, because I never wanted to write the damn book. I never wanted to have this thing to write about. So it’s a conundrum. What do I do with that? I hate those congratulation confetti things that show up on social media posts, although I love the people who post them and their efforts at being supportive.

You know what’s hard though? You have to do a certain amount of shameless self-promotion when you write a book, or nobody will ever see it. So when you do some of that and you post a snippet of a review that you were thrilled by, and you get comments like, “Oh, congratulations. Oh, I’m so happy for you.” That feels so weird. It is difficult to explain. I want people to read my book, but I don’t want all these happy congratulations, because I never wanted to write the damn book. I never wanted to have this thing to write about. So it’s a conundrum. What do I do with that? I hate those congratulation confetti things that show up on social media posts, although I love the people who post them and their efforts at being supportive.

Diane: I do want to congratulate you because what you did was very difficult, and what you’ve been through was incredibly difficult. And to use that old cliche, you made art out of pain, and you also created something that will help a lot of people. And that’s no small thing. That’s huge. And I congratulate you for that. I thank you for that.

Eileen: Thank you. Now, when you get back into being a therapist, I want you to know that I think you would be the best therapist a person could ask for. I feel like this whole conversation has been so therapeutic.

Diane: You know what? It’s really just two people talking heart-to-heart, and when we can make space for each other, for both the hard stuff and the joys, I think that’s what it’s all about. That’s where the healing takes place.

Eileen: I think you’re right.

As always, I’d love to hear from you. Please write a comment or send me an email.

See you soon!

XOXOXO

Diane

Thank you for sharing this beautiful conversation. And thank you for the pictures of Lydia. She is so beautiful and the pictures made me smile. Eileen, I was deeply moved by your obviously intuitive and sensitive parenting of your exceptional child. You were exactly the mother she needed. I was a therapist once, too, and want to apologize on behalf of all therapists for your awful experience in therapy. And I whole-heartedly disagree that all suicides can be prevented. I’m so sorry that this is the book that you had to write but I am so glad you wrote it. Blessings to you both!

Thank you, Sherry. And a big yes to “You were exactly the mother she needed.” What a beautiful thought and so very true.

Thank you so much, Sherry. Lydia also went through a few therapists before we found the one she would talk to. A wonderful therapist who made a huge difference. Still, in the long run, she could not stop it. I do believe if we’d made it to Lydia’s next scheduled appointment we might have been given more time. Another what-if I carry.

I loved this interview– felt like an honest, private conversation that I had the privilege of attending. Thank you Eileen and Diane. Eileen, you had me at “It’s not a chronological story. It moves around a bit, not unlike grief.” Well said. I’m looking forward to reading “Love in the Archives”.

Thanks so much, Stephanie. You will love the book!

This is a deep and insightful interview. Thanks to both of you for sharing yourselves.

Thank you, Karen, very much.

Thank you, Alison. I looked up Rosemary’s poetry. I am smitten.

What a beautiful interview. Maybe this (the interview) is the thing I’ve been needing to finally open my pre-order copy on my Kindle. My niece died by suicide fifteen years ago and my heart is still tender. Maybe your book Eileen will help me too. Thanks Diane. I think you’d make a fine therapist.

Thank you, Maureen. Of course your heart is still tender. Eileen’s book will help. Sending love.

Dear Maureen, our hearts will always be tender. And yes, the therapy world could use more Diane Gottliebs.

I sit here weeping. This is a beautiful interview. I echo the recommendation by Alison for Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer’s poetry.

Thank you, DeAnna. Rosemerry Waholta Trommer’s book is already on order!

I had the privilege of meeting both of you at Hippocamp, IRL, and I knew then you both were attuned to the human connection. What I didn’t know was your stories. Thank you Eileen and Diane for this beautiful and heartbreaking interview.

I loved meeting you and Eileen at Hippocamp, Trish. Such wonderful connections made there. Thanks so much for reading and for sharing your thoughts. XO

Thanks for reading, Trish. So glad we met. I hope to see you there again sometime.

What a painful and honest and beautiful interview. “There was nothing I could take away from her that would have made a difference.” This line, especially, haunts me. It’s true. And suicide is not all preventable – what a bunch of crap that is. Are you familiar with Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer’s poetry? She, too, had a child who died of suicide, and she never shies away from writing about it. Love and strength to both of you.

Thank you, dear Alison. I am running to check out Rosemary Wahtola Trommer’s poetry! So much love and strength to you.