Interview with Ana Maria Spagna

Ana Maria Spagna is definitely one of my sheroes. She’s a great model for following your passions, stepping into the scary places, and for living with the utmost integrity. Ana Maria was a writing mentor of mine at Antioch, Los Angeles. She’s a wonderful teacher, who’s generous and thoughtful with her feedback, and who always challenged me to take my writing to the next level. I’ve learned a great deal from reading her writing as well: about lyricism, about braiding ideas and themes, and about being courageous on the page.

Ana Maria Spagna is definitely one of my sheroes. She’s a great model for following your passions, stepping into the scary places, and for living with the utmost integrity. Ana Maria was a writing mentor of mine at Antioch, Los Angeles. She’s a wonderful teacher, who’s generous and thoughtful with her feedback, and who always challenged me to take my writing to the next level. I’ve learned a great deal from reading her writing as well: about lyricism, about braiding ideas and themes, and about being courageous on the page.

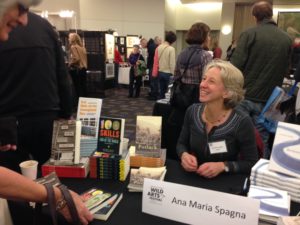

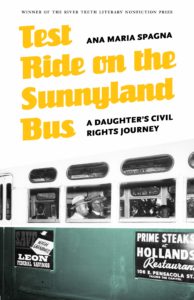

Ana Maria is the author of seven books including Uplake: Restless Essays of Coming and Going (see my review in last week’s post) , Reclaimers inspiring stories of elder women who persevered for decades to reclaim sacred land and water in the mountain ranges of the West Coast, and Test Ride on the Sunnyland Bus, winner of the River Teeth literary nonfiction prize, a brilliant blend of “cultural and personal history, memoir, and reportage” that chronicles Ana Maria’s journey from the remote Pacific Northwest to Tallahassee, Florida to learn about her dad and his role in an lesser-known story of the Civil Rights movement. Ana Maria has also published over 100 essays and stories on “wilderness, work, community, civil rights, and the complicated ways people protect what they love.”

Ana Maria is the author of seven books including Uplake: Restless Essays of Coming and Going (see my review in last week’s post) , Reclaimers inspiring stories of elder women who persevered for decades to reclaim sacred land and water in the mountain ranges of the West Coast, and Test Ride on the Sunnyland Bus, winner of the River Teeth literary nonfiction prize, a brilliant blend of “cultural and personal history, memoir, and reportage” that chronicles Ana Maria’s journey from the remote Pacific Northwest to Tallahassee, Florida to learn about her dad and his role in an lesser-known story of the Civil Rights movement. Ana Maria has also published over 100 essays and stories on “wilderness, work, community, civil rights, and the complicated ways people protect what they love.”

Ana Maria’s work has been recognized by the Society for Environmental Journalists, Nautilus Book Awards, and as a four-time finalist for the Washington State Book Award. She teaches in the MFA programs at Antioch University, Los Angeles and Western Colorado University and lives in the North Cascades with her wife.

I had the honor and pleasure of interviewing Ana Maria Spagna on FaceTime last month.

Diane: Hi, Ana Maria! It’s so great to see you! How are you?

Ana Maria: I’m good. It’s insanely hot here, so I’m in the cool house.

Diane: How hot?

Ana Maria: 102. Real hot. How about there?

Diane: Well, I’m actually in upstate New York where it’s in the 50s. Yeah, I’m in a hotel room, wearing a jacket. Oh my God! 102!

Ana Maria: You’re just bragging.

Diane: I am bragging. Ana Maria, I want to thank you for doing this.

I just want to say I’m really excited about this interview. I’m going to let everyone know that you were my mentor for two project periods at Antioch. And it was a wonderful experience.

I want to talk to you about your writing, but because this is a blog for women over 50, I want to talk to you about that too—I think you have a lot to offer us in terms of that as well.

Let’s just get a little bit of your background because it’s so interesting. So, you grew up in suburbia. Right?

Ana Maria: I did. Very much so.

Diane: So, how did you end up in the woods?

“Other Kids in High School Sketch a Boy’s Name on Their Folders. I Drew Pictures of Munson Falls”

Ana Maria: I was actually really happy in suburbia. I grew up riding my bike to the park, taking swimming lessons in the morning, playing tennis all afternoon. I mean, I had no beef with my upbringing.

My dad died when I was 11, which was formative. When I was about 13, a family that I babysat for took me on a trip to Oregon. It was ostensibly to babysit, but I think they knew that maybe I could use the trip. And I don’t know what happened. I mean, all I can compare it to is falling in love. I was just crazy excited about this landscape and the things that I saw.

Then we camped, which was something my family didn’t do, and we saw lakes and rivers and big trees and waterfalls, and I came back and had it in my mind then that whenever I was old enough, I’d be able to go to Oregon and go to college, which is what I ended up doing. Other kids in high school sketch a boy’s name on their folders. I drew pictures of Munson Falls, which was this waterfall we had visited. I ended up in Oregon for college and then after that working for the National Park Service.

“To End Up in This Lush Place … Was Like Walking into a Fairy Tale

Diane: Where did you go to school?

Ana Maria: I went to the University of Oregon in Eugene, and there’s no overstating how magical that landscape was for me. I was from the desert. I was from a smoggy area in LA. And to end up in this lush place, with rivers and big trees and open space and a bunch of hippies, was like walking into a fairy tale. It was exactly like walking into Oz. It was just seemed unreal to me and magical.

Diane: And so what did you do when you graduated? Did you stay?

Ana Maria: No, I didn’t know what I would do. I had an English degree, and what do you do with that? And so, I tore a postcard off of one of those bulletin boards we had back then, to volunteer in a National Park. I wrote down three national parks, because I visited them as a kid. My family did take us on road trips to St. Louis every year, and we visited national parks. I wrote down the Grand Canyon and Zion, which are big parks, and then Canyonlands because that sounded like a good name. And the only requirement was you had to be able to drive a stick shift. I thought that, “Well, I can do that.”

I landed in Canyonlands, which is this amazing place, for six months, as a volunteer and thought I would stay there my whole life. Then, by another freak of fate, didn’t end up staying there but ended up getting a job here in Stehekin, where I’ve stayed more or less ever since. So, going on 30 years.

“I Saw These People Who Were Paid to be Outside. I Wanted to do That”

Diane: You worked with a lot of men at the time?

Diane: You worked with a lot of men at the time?

Ana Maria: At that time, Diane, I didn’t. I had a female roommate in Canyonlands and was alone a lot. I liked solitude. I camped and hiked by myself. It wasn’t until I started working on trail crews, which is a laborer’s job as opposed to a ranger. … When I started working for the Park Service, I worked as what they call an interpreter. I gave guide walks and worked at the Visitor’s Center. I just thought that was terribly boring. I saw these people who were paid to be outside. I wanted to do that. It was once I started doing that work that I was around a lot of men.

Diane: And that was a bunch of years ago. Right?

Ana Maria: Yeah, that would have started in 1990. So, yeah, a lot of years ago.

Diane:

So you’re a trailblazer in more ways than one, right? Working in the trails and …

Ana Maria: It didn’t feel like it at that time.

There Are Always a Few Women, But It’s Definitely Dominated by a Macho Sensibility

Ana Maria: The real trailblazers had come maybe 20 years earlier in the early 70s. and we met those women. We really felt like they had forged a trail for us. It’s stunning to me now, how slow the progress has been. It’s still the same percentage of women, more or less, that it was in the early 90s. I haven’t looked at numbers, but that’s how it feels. There are always a few women but it’s definitely dominated by a macho sensibility.

Diane: Did you adopt that macho sensibility?

Ana Maria: You have to.

Diane: You have to. Right?

Ana Maria: Yeah. You both adopt it and you subvert it. You make fun of it. I’m pretty okay at making fun of it. My wife Laurie is exceptionally good at making fun of it. One of my very favorite memories is when we went to shovel a bridge in winter, which is a story of itself. Quite a journey to get there, quite a big deal to be out in the middle of winter, shoveling snow off this bridge, and there was a mix of paid people and volunteers. One of the volunteers, an older guy, was trying to show Laurie how to use a snow shovel, and instead of getting riled up—I would have just gotten pissed and turned my back—she said, “Oh, I know what you mean.” And she just spread her legs, bent over, and started shoveling backwards through her legs! It’s subverting that idea that you don’t know what you’re doing. Obviously, you do.

“I Just Rode My Bike 10 Miles Up This Dirt Road after Work and Then Back to Work in the Morning”

Diane: You met Laurie at work?

Ana Maria: We met my first year here, when I was still working in the ranger station and she was on trail crew. She was part of why I thought, “Oh, yeah, that trail crew. That’s the way to go.” My housing was down closer to the town, and she was way up in a backcountry cabin, 10 miles up a dirt road. I asked if I could move up there because it was closer to the woods, and the rangers said, “You can, but you’re not getting a car.” And I was like, “I don’t need one.” So I just rode my bike 10 miles up this dirt road after work and then back to work in the morning.

Diane: That biking’s a day’s work in itself, right?

Ana Maria:

I know, but it was a whole lot easier than being in an office for a 23 year old. Laurie and I were just friends that summer and then slowly but surely realized that we were falling in love, which was terrifying, absolutely terrifying.

Diane: Was this your first relationship with a woman?

Ana Maria: It was mine and hers, and so we were in this completely new terrain and it was shocking and scary and all of those things. It took a lot of courage and a lot of faith in each other to make it through. It was also the fact that we were here in this magical place. That helped a lot. We had pressure from the outside world, but we were in in the woods. That helped.

“I Am So Amazed at All the Things That Have Changed Over the Course of Our Lives”

Diane: When did you tell your families?

Diane: When did you tell your families?

Ana Maria: It probably took a year or two to tell our families. And that went poorly in the ways that often goes poorly. And, also went well in the sense that they love us, they still love us. We’re still close to them. But it was challenging. And I am so amazed of all the things that have changed over the course of our lives, that this has become so much easier. Seemingly for young people than it was then, which is wonderful.

Diane: The whole marriage thing was just all of a sudden, “Yeah, you guys can get married, right?” Did you ever think you would see that in your lifetime?

Ana Maria: Never. Absolutely, positively, never. It seemed—the word I use in Uplake is preposterous. It seemed preposterous, that that would ever become legal. When we got domestic partnership, in the mid 2000s in Washington State, and we had to … I guess this little story is the first indication that I thought it might all be okay. We had to get our domestic partnership notarized. And the only notary was a super conservative friend of ours named Roberta. I had to go over to her house. She asked to look at all the paperwork and was very businesslike. That’s what I expected. She’d be businesslike, she would stamp it, and I’d be on my way. But as I was leaving, she patted my shoulder and she said, “Hey, congratulations.” And I thought, “Wow!”

Diane: If you can hear that from her, right?

“I’ve Always Thought That Those Two Camps Share a Lot of Values”

Ana Maria: If you can get that from her, it was an indication of what was to come. Knowing people, personally, who found it acceptable. Laurie and I had not been loudly out, but we were never closeted even in this small place. Maybe when our neighbors could know someone gay, it made it a whole different story than if it’s the “other” that you think.

Diane: That’s interesting. You had expressed before that where you live, it’s like two camps of thought, the progressive, maybe hippie-ish, and then the … I don’t know, how would you describe the other camp.

Ana Maria: Maybe like libertarians. But the interesting thing about that is that I’ve always thought that those two camps share a lot of values. We share values of independence and of eating good food and of being outdoors. We’ve got a lot of common ground. I don’t like to overstate the rift because I think the rift is much bigger in places where people don’t interact like we interact with each other.

It’s Really Hard to Dismiss Someone’s Beliefs When You See Them Earnestly Working Within That Framework, Within Lives Full of Love and Full of Hard Work

Diane: I was going to ask you, what we can learn from how you guys all get along. It’s about getting to know people individually that makes all the difference?

Ana Maria: Yeah. I think that’s it. You have to interact here, no matter what, and it seems like that’s been lost in other places. I think there used to be gathering places, whether they were public schools, or churches, whatever those common places were, and I really feel out of my realm discussing how other places work. But here it works that we’re all have to see each other and have to talk to each other and know each other really well.

“We Don’t Talk About Politics. I mean, That’s the Secret to It All”

It’s really hard to dismiss someone’s beliefs when you see them earnestly working within that framework, within lives full of love and full of hard work. We all are just trying to do our best in this world. It’s very hard to judge that harshly. It’s a tough dance. It also doesn’t mean that we talk about our differences all the time.

Diane: You don’t talk politics, I’m guessing.

Ana Maria: No. People come in wide-eyed having read my books, and they’re like, “Oh, you must have such wonderful, interesting conversations with your neighbors.” I say, “No.” We talk about how many geese are in the lake, or what you’re growing in the garden. We don’t talk about politics. I mean, that’s the secret to it all.

Diane: So we know how you got to love the woods. What about writing? I know you were an English major. Were you writing in college as well?

Ana Maria: I was. I think when I was a really little kid, I really wanted to be a writer. I wanted to be John-Boy Walton, my mom will affirm that.

Diane: Oh my God! I had such a crush.

“But Then Like a Lot of Girls, I Just Lost My Confidence … or Lost My Passion”

Ana Maria: And I sat in a beanbag in second grade and wrote a novel and my teacher mimeographed it on those purple sheets and she gave it to everybody. I was really convinced that’s what I wanted to do. But then like a lot of girls, I just lost my confidence, I think, or lost my passion. It’s hard to define exactly what happens. But I just didn’t feel like a writer was something I could be.

I didn’t know what I would be. I was just swimming in those waters of adolescence. And then I thought, “Well, this will be it in college. I’ll be an English major, and then I’ll do a bunch of writing.” Where you do, but you’re just analyzing literature. That’s not your own creative voice. And so, the wonderful thing that happened is that when I went through all these tumultuous things—moving to the woods and falling in love with Laurie—the first thing I wanted to do was start to write. I started keeping notebooks and started writing. But even I could tell it was not very good. I wanted to say something, but I didn’t know how.

“It Was a Sense of Camaraderie … They’re Still My Closest Writing Friends”

So, I went back to graduate school to study creative writing, and I learned how to make a story, how to shape the story, things you think you would know from a lifetime of reading, but you don’t. And also, as you’ve recently experienced, I found a community of people, other people who were trying to do what I was trying to do and caring about writing the way that I cared about writing and-

So, I went back to graduate school to study creative writing, and I learned how to make a story, how to shape the story, things you think you would know from a lifetime of reading, but you don’t. And also, as you’ve recently experienced, I found a community of people, other people who were trying to do what I was trying to do and caring about writing the way that I cared about writing and-

Diane: Isn’t amazing? It’s so amazing, right?

Ana Maria: It’s amazing, yes, and, for me, it was much greater than the mentorship or the teaching that I got. It was a sense of camaraderie and those friends, they’re still my closest writing friends. They’re people I would trust with a manuscript first. And this is now more than 25 years ago.

I went where I could get paid as a teaching assistant, and we went to Arizona because Laurie’s grandmother was nearing 100 and still living alone in Phoenix. We could live in Flagstaff and go down and spend weekends with Ethel watching Lawrence Welk or watching golf.

Diane: Sounds dreamy!

Ana Maria: It was fantastic. It was a great connection for Laurie. Those were a couple of wonderful winters. I was studying fiction, but almost immediately after I graduated—or shortly before—I realized that I was a better essay writer.

Ana Maria: It was fantastic. It was a great connection for Laurie. Those were a couple of wonderful winters. I was studying fiction, but almost immediately after I graduated—or shortly before—I realized that I was a better essay writer.

Diane: I’m familiar with a bunch of your books, and I’m just thinking now, is Test Ride the only non-essay book?

Ana Maria: Also Reclaimers.

Diane: Reclaimers! That’s right. But that’s also a few different stories, right?

Ana Maria: Yeah. It’s a few different stories braided together. I think of Reclaimers as narrative nonfiction. And I think of Test Ride as a memoir/history. And then the three collections of essays are different animals.

“The One Rule I Have Is, If Anybody Asks You, ‘Do You?’ … You Say ‘Yes!’”

Diane: And you wrote a young adult novel?

Ana Maria: I did. And that one took forever. I started very shortly after graduate school. I had been writing a short story about a character named Charlotte in her early 20s. And an editor contacted me. This hardly ever happens, so don’t get any glamorous ideas. But an editor contacted me and said, “Do you ever write young adult stuff?” And the one rule I have is, if anybody asks you, “Do you?”

Diane: You say yes.

Ana Maria:

Of course, you say yes! So, I said, “Yes.” And then I thought, “Oh, God, what have I done?” And I went back and looked at Charlotte, and I was like, “Oh she’s not 22. She’s 14.” And it was so easy to make her 14, and to write this short which they accepted. And then from then on, whenever I had a break from my nonfiction writing, I went back and spent time with Charlotte. It took a long time, but I loved writing The Luckiest Scar on Earth

Of course, you say yes! So, I said, “Yes.” And then I thought, “Oh, God, what have I done?” And I went back and looked at Charlotte, and I was like, “Oh she’s not 22. She’s 14.” And it was so easy to make her 14, and to write this short which they accepted. And then from then on, whenever I had a break from my nonfiction writing, I went back and spent time with Charlotte. It took a long time, but I loved writing The Luckiest Scar on Earth

Diane: Do you think you’ll go back to fiction?

Ana Maria: I don’t know. Right now, I’m messing around in poetry.

“Poetry Feels Like Going Back to the Playground”

Diane: Tell me about that. How’s that going?

Ana Maria: It’s going great. I think one of the things that has happened to me with nonfiction is that there’s a lot of expectation around it. I used to be able to write and who knew who was going to read it, especially pre-internet? It was like: it’s going to be in a little literary journal, I know nobody will see it. But now everybody sees it and has expectations about what I’m going to write, and that puts certain constraints around what I write or how I express myself. Poetry feels like going back to the playground. Like, “Let’s just play. Nobody’s ever going to see this.”

Diane: That’s great.

Ana Maria: Yeah. It unlocks that place. Which is what we all want. We want it to be unlocked.

Diane: You write so lyrically in your nonfiction.

Ana Maria: Thank you.

Diane: You do. Beautifully. And I’m wondering if poetry has even made that stronger?

Ana Maria: I think it might have given me another way to understand something that’s come naturally to me. Probably you found this in graduate school, that things you’ve been doing all your life, you don’t have a name for them, or you don’t know what they are or where to put them necessarily. They’re just how you write. Having names for the lyrical language or ways to use it, has been exciting.

“I Have to Be Reading New Things. I Have to Be Thinking in New Ways”

Diane: And what about teaching for you?

Diane: And what about teaching for you?

Ana Maria:

I love it. I absolutely love it. A lot of people feel that it steals the same energy that they use in their writing, but I don’t feel that way. It energizes me; it gives me a similar camaraderie that I had in graduate school with my fellow students. And of course, you’re helping someone, which is fantastic. It keeps me on my toes. I have to be reading new things, I have to be thinking in new ways. I worry a lot about my own work calcifying, and I worry about my teaching calcifying. So, I’m always trying to stay a step ahead. Teaching is wonderful for that.

Diane: You are wonderful teacher!

Ana Maria: Well, thank you. I do want to say that I am also a spoiled teacher, and that it is much easier for me to say those things when I have 6 or 12 students than someone at a high school or community college with hundreds of students at a time.

Diane: And you teach undergrad too, right?

Ana Maria: I have. I come and go whenever the opportunity arises. I’ve taught online classes for community colleges, and then I did a visiting job at Whitman College and in Montana, so yeah, I have. But the main focus of my work has been with graduate students and, or, with continuing education. I worked for many years for Gotham Writers Workshop online.

Diane: I’ve taken some things with them!

Ana Maria: I did it for years.

“Getting that Taste of the World Is Important”

Diane: Wow! How fun was that?

Ana Maria:

It really was. And especially back then, because when I started with them we had just gotten internet here, and so, I went from a very isolated, just camping with two or three people for weeks at a time, all summer, and then living with Laurie, and then suddenly had students in Australia, and South Africa, and New York. So, it broadened my horizons really fast at that point.

Diane: When you go to Antioch. How is leaving where you are and going to a city in California?

Ana Maria: It’s crucial. It’s really good for me because I live in a very small place. There are 80 people who live here year-round, and there are no roads in or out. And it’s wonderfully remote, but it’s also very remote. And so, getting that taste of the world is important, and I find Los Angeles in particular super invigorating. Which is ironic because I grew up near there and really pooh-poohed it, as you do when you’re in your 20s. You pooh-pooh wherever you’re from. But now I find it marvelously diverse and vibrant and challenging, and I just adore being there.

Diane: It’s a good balance, right?

Ana Maria: It’s a super good balance. I can come back to the woods, and then be there and enjoy it. And also, I don’t have to drive when I’m there, which is fantastic.

“I’m Surrounded by Women Who Have Done Amazing Things Beyond 50”

Diane: So, tell me how you feel about being on the other side of 50 and what that is like for you. I think it’s very liberating, do you?

Diane: So, tell me how you feel about being on the other side of 50 and what that is like for you. I think it’s very liberating, do you?

Ana Maria: I definitely do. Part of why I feel that way is because I’m surrounded by women who have done amazing things beyond 50. I see people remaking themselves in various ways, and I feel that within myself, particularly when I went to Walla Walla to work at Whitman. I had to move out of my woodsy house for a year, and live in a little town, and it felt like the right time to do that—a lot like that period of time when I was leaving home and going to college. Not just because of the leaving, but something about being this age, and menopause and changes happening. I just find a lot of delight in it, watching my friends do fantastic things and people who are 20 and 30 years beyond me doing fantastic things.

Diane: Isn’t that amazing?

Ana Maria:

Yeah. I have one friend who was an elementary school teacher for years and then she went back and got her PhD because she wanted to help others teach math better. She has a passion for teaching math, so she went and got a job as a professor at over 50. And I think, that’s so inspiring.

Diane: It’s amazing.

Ana Maria:

And I want to tell you about another friend who took up ice hockey when she turned 50, and she’s now over 65 and still playing hockey.

Diane: Wow! Good for her.

Ana Maria:

I know. It’s fantastic.

“I Just Never Questioned that Adulthood Would Be Different for a Woman”

Diane: I always ask people, who their female models were. You mentioned that that your dad died when you were 11. So, your mom had lot of stuff to do with 3 small kids. Do you feel like she helped you be the woman you are?

Ana Maria:

Surely. Absolutely. Even the person that she was before my dad died. I don’t know how she did it. She was from a family of immigrants in St. Louis. All of her family, including her extended family, stayed in St. Louis. And somehow, she had the guts when she was 22 years old to get on a DC-3 and fly to South America on a Fulbright. That’s where she met my dad. That example was always in our life, and then seeing her have to take over and be the person that she was with three little kids. I was 11. Lisa was nine. My brother was five when my dad died, and now I hear her say how hard that was. At the time, I was like, “Of course, my mom can do all these things.” She was always this amazing independent person and expected that of us but not in a demanding way.

My warmest memories are sitting around the dinner table or around the breakfast table talking politics. She treated us as adults or as peers in a way, and that was marvelous. I just never questioned that adulthood would be different for a woman. In fact, it was hard for me when I got to college, and I would read feminist writers. I thought, “Well, there’s no oppression of women, women can do anything.” And it took me a long time to realize, “Well, that’s not exactly true.”

“It Took Me a Long Time to Realize that I Was Writing Like a White Male Writer”

Diane: I was listening to a replay of an interview with Toni Morrison, where I think she said that it was Doctorow who said, “When I read her, I don’t think of a woman writer, I don’t think of an African American writer, I think of … ” And she jumped in and said, “A white male writer? Do you see me as a white male writer?” And so, you’ve been at this writing thing for a while. Have you experienced that kind of stuff?

Ana Maria: It took me a long time to realize that I was writing like a white male writer. That was the only writer in my head. As much as I loved Virginia Woolf or other women writers, when I was young, the default, the blank slate is still a white male voice, right?

And so, to take that by its reins and say, “No, I am another thing,” and to keep emphasizing that has been a long journey for me. You work really hard when you’re on an all-male crew, to just be a crew member. You’re not the girl on the crew. You’re just one of the crew. But at some point, you have to recognize: I am the woman on this crew.

Diane: You are the girl on the crew.

Ana Maria: I actually am a woman on this crew. I am not the girl on this crew. I am the woman on this crew.

Diane: The woman. Okay! There you go. I bet that’s a very important difference.

Ana Maria: It is a big difference.

“You Have to Make People Realize that White Male is Not the Default, Right? To Embody the Variants … Not Just the Universality.”

Diane: When you’re surrounded by men it’s important to be seen as a woman and not a girl, right?

Diane: When you’re surrounded by men it’s important to be seen as a woman and not a girl, right?

Ana Maria:

A girl is a diminutive. A girl doesn’t necessarily have to pick up the chainsaw. Girls don’t run saws, or it’s cute when they do. It’s something that has to be dealt with. And the same with the gay identity. I used to bristle at how every time I would write something or bring it to workshop, people would say, “I didn’t know you were gay. You should have put that in the front.” I thought, ” Honestly, I don’t have to write it every single time” and now I think, “Yes, you do. You have to. You have to make people realize that white male is not the default, right? To embody the variants, that are your own and not just the universality.”

Diane: Do you think things are changing?

Ana Maria: I do, but I think they’re changing as a result of-

Diane: Of doing that.

Ana Maria:

I used to have a lot more faith that they would just change. But they don’t change with silence. You do have to speak up.

Diane: Nothing does, unfortunately.

Ana Maria: You don’t have to use a bullhorn, but you do have to say it, and that’s still a challenge for me. I’m conflict averse. I like to smooth things over, and it’s hard.

“The Journey and the Practice is Its Own thing. Wherever It Takes Me Is Okay”

Diane: Do you have a favorite thing you’ve written?

Diane: Do you have a favorite thing you’ve written?

Ana Maria: I’m most proud of Test Ride, the book about my dad. It took a lot of courage, a lot of emotional courage. But then I’m like any other writer. The most recent thing you’ve written is what you love most. So right now, I really love Uplake, and I love the things that I’m working on currently. I hope that will always be true.

Diane: It has to be, right? What are you doing now?

Ana Maria:

I’m in the midst of a big project about Chinese miners along the Columbia River near where I live. Here in North Central Washington, there was a massacre in 1875 of Chinese miners. It’s very hard to find the details. Some histories say Indians did it, some say white people did it. Some historians say that it could not have happened at all. So, I’m navigating that story, trying to figure out how that works with the way our contemporary ideas, or people’s ideas always are about immigrants, works with xenophobia. It’s a whole new realm for me, which is exciting.

Diane: Exciting!

Diane: Exciting!

Ana Maria: I don’t know what it is, but it’s something.

Diane: It’ll show itself, right? Do you trust that things show themselves?

Ana Maria: I do finally. I really do. I bet that comes with also thinking, if it doesn’t, it doesn’t, right?

The journey and the practice is its own thing. Wherever it takes me is okay. Which is a nice place to be.

Diane: That’s a wonderful place to be. And you know what? I think that’s a wonderful place to end.

Ana Maria: Excellent. Thank you.

Diane: I so appreciate you doing this. Thank you so much. And I love seeing you. It’s wonderful.

You can learn more about Ana Maria Spagna at www.anamariaspagna.com and

https://www.antioch.edu/los-angeles/faculty/ana-maria-spagna/.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! Please leave a comment or send me an email.

Have a wonderful start to September, everyone!

See you next Friday!

Diane

Oh my goodness, Diane! Waking in the wee hours of the morning to check on news if a new president was announced while I was sleeping. I clicked on Safari and your podcast, dialed into this interview, came up!

Two of my favorite people having a conversation! Thank you for this inspiring read! XO

Thank you, Kathie!!! And you are one of our favorite people!! XO

From start to finish, this is a most engaging interview! Knowing the effects of mentor-mentee, I’m so happy that she was your mentor for two PP’s, like Alma was mine! I’ve always loved Ana Maria, and now I know why! This passion for teaching plus a deep love for nature, plus the knowledge humans are interdependent… stunning.

Thank you Diane, for this engrossing interview with Ana Maria. Although I know and love her already from my experiences with her at Antioch, as do you, I was thrilled that your conversation with her revealed a lot of new information about her and her background. I was fascinated by her Mom- her adventurous spirit and enormous strength and courage. I agree with Ana Maria about looking past political differences in our neighborhoods, to focus on all the facets of our lives that we have in common. Although it’s taken me a long time to be comfortable with my own public displays of political affiliation, I also know that bumper stickers and badges can provide excuses for us to dismiss others, and deepen political polarization.

Ana Maria writes beautifully and because of everything she taught me, I will always be in her debt. Everyone should read her work. If not immediately, very soon at the latest.

Thank you, my dear Sarita! Glad you learned some new info about Ana Maria! Her mom does seem like an amazing person (apples don’t fall far from their trees!).

LOVE what you said about political affiliation–so true–and, yes, everyone should read Ana Maria–“very soon at the latest.”